Despite pressure to support future development north of the Garibaldi Highlands, Squamish council decided to stay on the course, voting Tuesday to keep population barriers in the draft Official Community Plan.

The draft planning document’s “growth management strategy” currently includes a “threshold” that limits residential builds in certain areas until the population of the district reaches 34,000.

If the proposal provides “extraordinary community benefits” the population only needs to be 22,500 before council will consider the project.

The discussion on Tuesday was not focused on one particular development, but the policies adopted will have major implications for some Squamish landowners. The policy is still in a draft format – after Tuesday’s vote, it will go to public consultation.

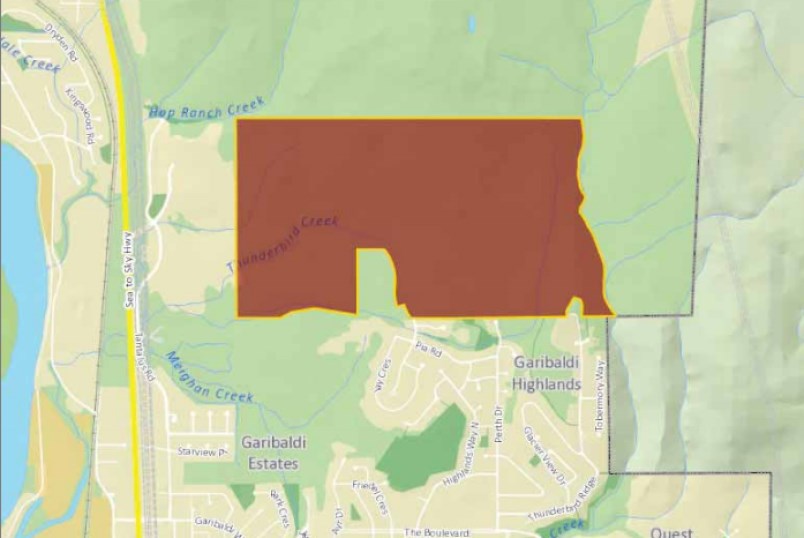

The Cheema family owns 400 acres north of the Garibaldi Highlands and spoke at length during the meeting. They were asking councillors to remove the 22,500 population threshold and change the wording of another policy that will restrict growth until certain conditions are met.

The lands have some crucial connecting mountain bike routes and trails, but the family has said they will need to close the trails for safety reasons if development is not possible.

The Cheemas’ request was supported by those behind the Squamish Off-Road Cycling Association and the Sp’akw’us 50 race. “The community is pushing for this because it will allow small businesses to grow and allow a connected Squamish through the trail network,” said Aran Cheema.

“Council should not fetter its discretion to look at a development application that can bring such extraordinary benefits to the community. At the end of the day, the council still has the full authority to reject or accept a development application,” he said.

Despite that, some councillors, including Coun. Karen Elliott, Doug Race, and Jason Blackman-Wulff, expressed concern about the pace of development in the district.

“My worry over time, if we don’t manage growth, is we will build have and have-not neighbourhoods,” said Elliott. “That’s my concern, that’s why I’ve held quite strongly to that population threshold. There’s already a lot of work to be done to make Squamish more livable.”

Staff said the reason behind the policy is to encourage infill development, making sure the costs of sprawl are balanced with the local tax base.

Slower growth would also allow the district to fill in some key policy gaps, including an affordable housing strategy, an updated wildfire plan and an inventory of important recreation sites.

Coun. Doug Race went as far as suggesting that council forget the population threshold and instead limit all development outside the existing growth area for three years.

Bob Cheema suggested putting up barriers to the development of his land would send a message that Squamish is “anti-bike” and threaten the tourism potential of the area.

He also said council would be turning down other “extraordinary community benefits,” including mountain biking trails supported and improved, space for recreation technology companies, affordable rental housing, a daycare and a K-12 school.

The Squamish Waldorf School has expressed interest in a new school on the land.

Even if the final version of Official Community Plan includes the population limit, future councils could still allow an amendment if they vote in favour of a development proposal.

Quest University, as an example, was outside the OCP when proposed but was given an exception.

The population threshold and the other conditions in the planning document are not finalized. The draft will go to second reading, and residents will have a chance to weigh in directly during public consultation.

District staff said 58 people have already made official comments about the policy, including 50 supporting the removal of the population threshold.

“I think of the community really objects to it, we’ll hear about it at the public hearing, but I think it would be unfair to take that out,” said Elliott.