When you walk into Grass Roots Medicinal in Squamish you only get access to the waiting room. There, a small counter offers bongs and other glassware for sale. All the good stuff – the grass the store gets its name from – is locked up behind a second door, out of reach. To get there, you have to sign up to become a member, which means providing some proof of ailment that cannibis might help you with.

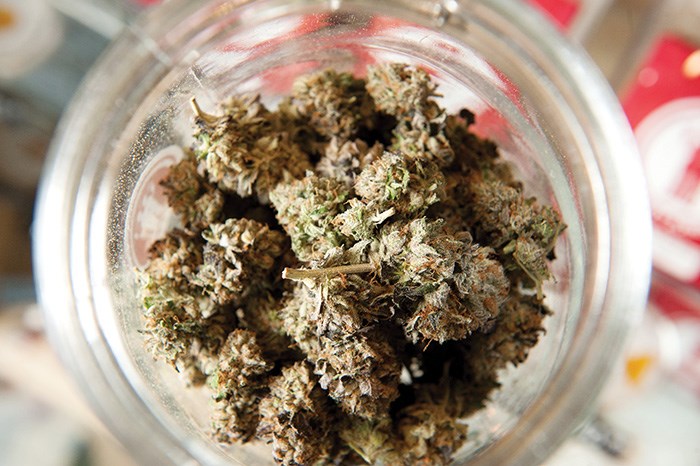

“We are strictly medicinal,” says co-owner Don Fauchon, who offers to unlock the door and give me a tour. Inside lies a plethora of products, spread out in an atmosphere as clean and clinical as a pharmacy. There are dozens of glass jars of cannabis flowers, running from ‘daytime’ selections that will keep you alert and creative, to others that will sink you into the couch, most for $10 a gram. There are sodas infused with cannabis, gluten-free cookies, and even dog treats (popular for owners who need to make a long trip and want their dog to be chill for the ride, says Fauchon). There are syringes of expensive oil concentrates that can be dropped onto ice and swallowed like a pill, and amber-coloured ‘shatter’ that looks like hardened sap. There are suppositories, to bypass the liver and avoid a high. The staff is keen to find just the right product for each of their nearly 1,000 members. While I’m there, for about an hour on a Saturday afternoon, a dozen customers come and go; the staff know all their names on sight.

Grass Roots (in a new building on Tantalus Road across the street from London Drugs) has a business licence to operate in Squamish, Fauchon tells me, costing them $5,000 a year. Even so, they are still technically illegal, as are all dispensaries in Canada. Although you can use medical marijuana in Canada, there’s only a few ways you can legally get it: You can register with Health Canada to grow it yourself; have a friend grow it for you; or buy it online from one of a handful of licensed producers (there are 23 of these in Ontario, a handful in other provinces and just eight in B.C., including the Whistler Medical Marijuana Corp). Anyone else, including Grass Roots, is operating in a hazy area: medical marijuana is legal, but the dispensaries are not.

This hasn’t stopped storefronts from sprouting up. At least four dispensaries have opened (and some have shut again) in Squamish over the last few years. Up the road in Pemberton, an offshoot of Vancouver’s SWED Society is trying to open doors — they have permission to sell glassware and paraphernalia, but not marijuana, as the Village of Pemberton just passed a bylaw to prohibit dispensaries. Google Maps lists more than a dozen shops in Vancouver (others have been shut down). Olympic gold medal-winning snowboarder Ross Rebagliati at one point planned to open a couple of Amsterdam-style weed coffee shops in Whistler. Although that fell through, he now runs a medical marijuana company called Ross’s Gold, with a flagship store in his home town of Kelowna.

All these shops are now awaiting a seismic shift in the landscape: Canada is going legal.

In April, the Liberal party is expected to announce legislation that will legalize marijuana by July 1, 2018. This follows Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s 2015 campaign promise to “legalize, regulate, and restrict access to marijuana,” to help keep it “out of the hands of children, and the profits out of the hands of criminals.”

Weed shops are surely bound to start popping up in B.C. like, well, weeds. Yet so much is still up in the air. Will a limited set of products, made by limited producers, become available only at government-run shops like liquor stores? Or will a craft-cannabis culture be supported, like the craft-beer industry? How will the government keep track of how strong and pure the marijuana on offer is? And will an increase in retail cannabis mean more people will start using, or start younger?

A grey market

For now, the legal grey area for medical marijuana means that things are very much in flux.

When I went looking for WeeMedical Society across from the local Wendy’s in Squamish, people in the neighbouring stores told me the dispensary had been shut down a few months ago. Just down the street from Grass Roots, next door to the Wiggin Pier fish-and-chip shop, the discrete Kaya Clinics has a sign saying it is open. But when I ring the doorbell, the manager unlocks the door to tell me he can’t actually sell any cannabis right now. This place has a clean and clinical feel but with the addition of a Buddha fountain tinkling away in the corner. The owner declines to speak to me.

Squamish’s director of community planning, Jonas Velaniskis, explains in an email that Kaya Clinics “is located in an area where marijuana dispensaries are not permitted as a land use pursuant to the zoning bylaw. A business licence for a dispensary cannot be issued in this location.”

The only other dispensary in operation is in downtown Squamish, right at the end of Second Avenue, down past the community garden and library. You can smell 99 North before you see it. “Customers say it smells like heaven,” says the woman behind the counter. She declined a formal interview and asked me not to take photos. Like Grass Roots, 99 North did brisk business while I was there, with half a dozen walk-ins over a half-hour on a Saturday. They are in the process of trying to get a business licence, according to Velaniskis.

This place looks more hippy than clinical in a cozy wooden shop next to a yoga studio. A medical cross decorates their storefront, but you don’t seem to need a doctor’s note here; the Squamish zoning bylaws do not differentiate between medical or recreational marijuana sales, Velaniskis explains: “For clarity, the bylaws allow marijuana sales for non-medicinal purposes. The bylaws permit ‘marijuana dispensaries’ in certain zones and subject to a number of significant conditions (such as proximity to schools).”

One customer tells me plainly she uses it recreationally. “Well, I get a headache when I have a hangover,” she laughs. She can get it from a dealer in bigger quantities for a cheaper price, she says, but she likes the selection at 99 North. (She declined to be named for this story). Others are clearly buying it for medicinal reasons, including one customer I met who says he uses it for post-traumatic stress disorder. The owner of 99 North declines to speak to me, saying that because of the nature of the business, he would need to consult his lawyer first.

Whether you need a medical reason – and the way you might prove that – is extremely variable from one dispensary to another. “If you’re being prescribed a pharmaceutical, then you could probably benefit from our products,” says Grass Roots assistant manager Tori Enns. “We like to keep the umbrella wide.” Some shops require a note from a doctor or they ask customers to describe their condition and symptoms in detail; others simply provide a list with boxes to tick, offering options from Multiple Sclerosis to “neck problems” or “sexual dysfunction.”

In general, if the shops are few, discrete, responsible, and even licensed, then the police seem to leave them alone. “I think the police like us because we put a couple of dealers out of business,” laughs Fauchon, though he adds that could be just a rumour. Grass Roots has revoked a few memberships, says Fauchon, when they caught customers handing their products over to a friend. The police threatened to shut 99 North soon after it opened in 2014, but two years later it is still open. “The bottom line is that marijuana is still illegal,” says Whistler RCMP operations NCO Scott Langtry. That’s pretty much all the police will officially tell me; Squamish RCMP declined to comment about whether or why any dispensaries were in operation in their jurisdiction.

The biggest obstacle seems to be not the police but local councils. Since Squamish passed a bylaw allowing dispensaries to apply for business licenses in July 2016, SWED Society optimistically assumed that Pemberton might do the same, says local manager Ginny Stratton; they invested in artwork and display cases for their store. But Pemberton’s council instead decided to join Whistler in not permitting dispensaries. Pemberton’s council told SWED they could apply for a Temporary Use Permit, but only if and when the federal legislation changes. The latter part of that condition could take years. So, for now, the SWED shop has brown paper taped over its windows and the door is locked.

Ironically, the only legal producer in the corridor, Whistler Medical Marijuana, declines to speak with me. The company grows about 1,000 plants, according to a 2016 CBC story, and lists prices of $9 to $13 per gram on their website. They are set to expand with a new growing facility in Pemberton in 2018. Like all legal producers, they do not sell from a storefront; customers have to register and order online. Dispensary proponents argue that the licensed producers fail patients by not being able to have a face-to-face consultation about their products.

Risks and benefits

For doctors, the system as it stands is frustrating, says Nick Fisher, one of the physicians at the Pemberton Medical Clinic. There is a huge spectrum of marijuana products with different percentages of cannabinoids: compounds like Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which hits the brain, and Cannabidiol (CBD), which doesn’t get you high. Different formulations have different effects, just like tequila might wake you up and gin might make you cry. Yet doctors can’t “prescribe” a given formulation, or say how often it should be taken or in what concentration; they just sign a piece of paper saying a patient can use medical marijuana. “That makes us uncomfortable,” he says.

The medical clinic gets about a dozen requests to sign such forms each year; in the handful of cases that Fisher has signed, it has been based on a long-term relationship with a patient where he can see that other options aren’t working. In some cases that’s because pharmaceuticals are so expensive. Nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid that can be prescribed for pain relief, might set a patient back $1,000 a month, says Fisher. “I remember wanting to prescribe it for someone and they said: ‘No, I’m not paying that. I can grow it in my garden.’”

In other cases, available pharmaceuticals come with nasty side-effects. “You look at marijuana and think, why not? Are the side effects going to be worse? Probably not,” says Fisher.

There can be problems. “Cannabis use disorder” is basically cannabis addiction; heavy users may experience withdrawal symptoms like anxiety or nausea. Fisher says he sees a couple of people with that problem regularly in Pemberton’s emergency ward. Marijuana use has been linked to schizophrenia in some studies, but an academic review on that topic says it’s not clear if the drug triggers the illness, or if people with the illness simply tend to like the drug. The same goes for links between marijuana and alcohol use and lower intelligence; it’s hard to say what is causing what.

The benefits, on the other hand, could be big. “Medicinal marijuana has an amazing potential, but very few randomized controlled trials,” notes Fisher. A 2015 review in JAMA, one of the largest international peer-reviewed medical journals, found solid evidence that marijuana helps people with nausea that stems from chemotherapy, chronic pain, neuropathic pain, and spasticity from Multiple Sclerosis. For a lot of other conditions for which marijuana tends to be promoted (including Parkinson’s disease and Tourette’s Syndrome), trial results have been conflicting or inconclusive. Legalizing marijuana, notes Fisher, will hopefully spur more studies that examine the specific compounds that have the best effect for specific diseases or symptoms.

Rocky Mountain high

Fortunately, Canada isn’t the first country to legalize medical or recreational marijuana. We have other examples to look to. Uruguay is the only country to have fully legalized the sale, cultivation and distribution of cannabis, which it did in 2013. In the Netherlands, surprisingly, it is still technically illegal. While the drug remains illegal at the federal level in the U.S., individual states are permitted to draft their own laws within certain limits.

Colorado is perhaps the perfect case study for B.C. Like here, it’s a mountainous area with its share of ski bums. Colorado also has the distinction of being the first state to permit sales of recreational marijuana as of 2014 as an adjunct to a long-standing medical marijuana law dating back to 2000. As of 2015, Colorado had more than 500 medical dispensaries.

Making these transitions wasn’t exactly easy, says Andrew Freedman by phone from Colorado, where he was formerly the state’s director of marijuana coordination and now runs Freedman and Koski Inc., a consulting business to assist communities with the transition to legalized marijuana.

“You need an entire regulatory system overnight, and that’s unique. Usually it’s an evolving process to regulate a product. Lab testing, pesticide use, potency, public-health studies: most of those things exist over a long period of time, but none of it exists for marijuana,” Freedman says.

“I think we were fairly fearful of dramatic consequences, but we haven’t seen those,” he says of Colorado’s move to legalization. “It has been a fairly smooth road. Not that there weren’t a few bumps.”

The Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center saw a 70-per-cent boost in calls related to marijuana in 2015 compared to 2013. And soon after Colorado’s 2014 legalization, there were two deaths linked to marijuana edibles: one person committed suicide, and another allegedly killed his wife after ingesting marijuana cookies and candy. Accidental overdoses are also a concern with food products, such as hash brownies – particularly for kids who might not know what they’re eating from Mom or Dad’s stash.

What about usage? Right now, about half of Canada’s youth report that marijuana is easily accessible, and Canada has the highest rate of adolescent marijuana use of any developed nation. That said, the percentage of people who say they’ve used it in the last year is higher in both the U.S. and New Zealand than in Canada.

Perhaps surprisingly, state-wide surveys in Colorado show that kids don’t start using more of the drug because it is more widely available. If anything, there is a small decline in youth use. “I’d say it’s way too early to tell what’s really going on,” says Freedman. Since it is illegal for kids to buy marijuana in Colorado, their access to the drug hasn’t really changed. But the legalization for adults could make the drug more desirable. Conversely, as marijuana is legalized, perhaps it loses its allure of being forbidden — and becomes less desirable.

“Public-health officials say that changing attitudes takes a long period of time, so that’s going to take a while to come through,” says Freedman. “It’s too early to say what will win out.”

Other jurisdictions have not witnessed a surge in usage after legalizing marijuana. Across the pond in England, for example, a study of their decriminalization legislation in 2004 found no increase in marijuana usage, or in crime or anti-social behaviour. Other studies have shown that, in general, an uptick in the number of medical marijuana dispensaries tends to be related to a decrease in crime — perhaps in part because people might drink less alcohol if they have better access to pot. But the statistics are confusing, and while some people swap booze for pot, others tend to drink more when they get high.

There’s no solid evidence that marijuana is a “gateway” drug to harder drugs. In fact, it’s possible that making marijuana more easily accessible might drive people away from bad habits. One recent study in 50 U.S. states over a 10-year period found a 25-per-cent reduction in opioid-related overdose deaths in those states that had medical marijuana laws in place, compared to those that didn’t.

Pure and potent

Likely the biggest problem with either medical marijuana or recreational marijuana seems to be not knowing exactly what’s in the product. Lab tests can determine how much THC and CBD is in any given product, and whether it is contaminated with bacteria, mould or residual pesticides. But that testing is expensive, so not everyone does it.

Right now, the handful of licensed producers must abide by regulations set by Health Canada. Producers are responsible for their own testing, either by performing it themselves or farming it out to a trusted lab, and they must maintain records for potential audits. Health Canada makes both scheduled and surprise inspections. Since 2013, there have been 11 voluntary recalls of products from licensed producers across the country (at least one from the Whistler Medical Marijuana Corp. in 2014), because of mould, bacteria, or mislabelled amounts of THC or CDB.

To date, Health Canada has only required licensed producers to test for residues of 13 approved pesticides. Some critics say that’s a problem since other pesticides — including one called myclobutanil that turned up in some of Colorado’s dispensary cannabis — are known to be used by growers. Health Canada tells Pique they will undertake “random testing of product from all licensed producers for myclobutanil and other unauthorized pesticides.” The Whistler Medical Marijuana Corp. says its product is certified organic, and doesn’t use pesticides.

Meanwhile the dispensaries, being illegal, aren’t subject to any formal regulation. And while a storefront owner might have the best of intentions, they might not know exactly what is in their product. Fauchon says that Grass Roots uses a Health-Canada-certified lab on Vancouver Island to perform tests for them, and has never had a product test positive for contamination.

But a 2016 Globe and Mail investigation of Toronto cannabis dispensaries found three of the nine shops from which they purchased product wouldn’t have passed Health Canada safety guidelines. Three dispensaries tested positive for excessive amounts of bacteria, and one dispensary tested positive for yeast or mould. A similar report in Vancouver found that only six of 22 dispensary samples would have passed Health Canada tests.

Jonathan Page, an adjunct professor of botony at the University of British Columbia, opened his own cannabis testing company, Anandia Labs, in August 2016 to help meet anticipated demand. So far, his customers include eight licensed producers from across the country, and dozens of private growers who want to know what’s in their own plants. It costs between $500 and $1,000 to test a batch, Page notes, so private growers typically opt for the cheaper tests for potency, and test their plants just once.

“I think Health Canada should have realized some time ago that patients in some parts — Vancouver in particular — get their cannabis from dispensaries. There’s variable quality control in that market. Testing could help to improve that situation,” Page says. Although the government doesn’t permit certified labs such as Page’s to conduct testing for illegal dispensaries, he suspects that some of the private growers who use his services are selling to the dispensaries, so those products would at least have a measured amount of THC, for example. Other growers or dispensaries might be testing “under the table” at other labs.

The system, says Page, doesn’t acknowledge the realities in B.C., where cannabis cultivation has long been a huge business. A federal government Task Force on Cannabis Legalization and Regulation in 2016 said it would prefer a system that allowed for small, medium and large companies, including mom-and-pop producers. “But that’s not what we have now,” says Page. “There’s a worry that everyone will get shut down except for the big producers.” It’s a hard club to get into: Health Canada has had 1,611 applications from those interested in becoming licensed producers, of which only 38 have been approved.

Fauchon, who is also chairman of the Cannabis Growers of Canada organization, says he is already talking to politicians and petitioning to keep the “little guy” included in future systems. “There are probably about two dozen around here, just growing a little extra in their basements,” says Fauchon. A recent Cannabis Growers of Canada study found at least 13,500 small-to-medium growers in B.C. If they’re not allowed to continue a “craft cannabis” industry, Fauchon says, then a black market will persist even after legalization.

Regardless of how the laws and regulations pan out, marijuana use seems unlikely to explode. Page says he grew up on Vancouver Island with a lot of marijuana around, and now, he says: “My life is kind of centred around cannabis.” But he hasn’t become a pot head. “People assume I’m a big user, but I’m not,” he says. “Alcohol is my drug of choice.”