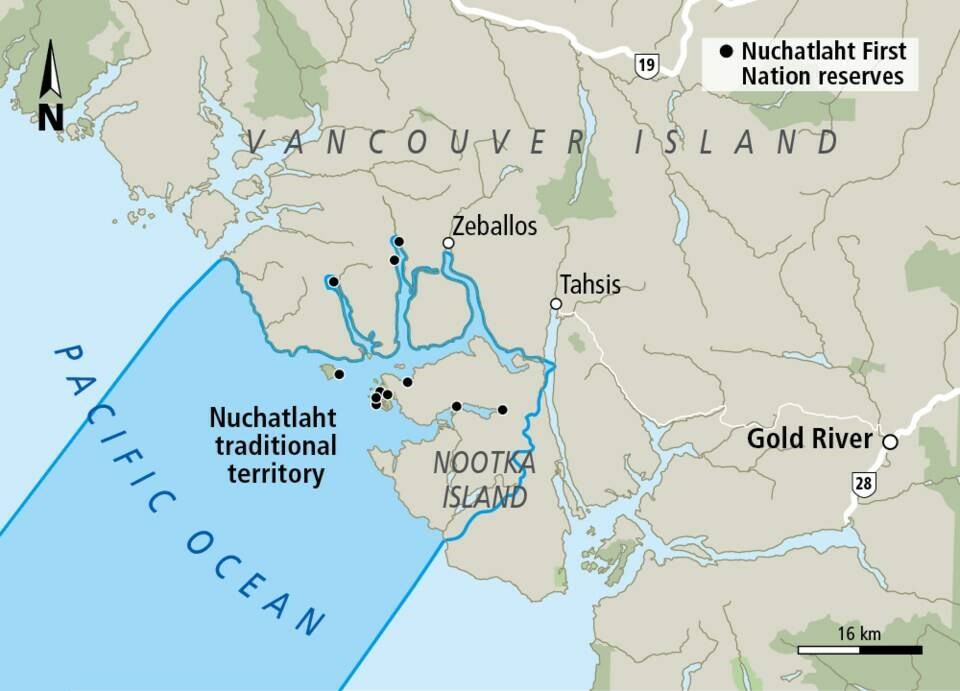

Representatives of a small First Nation say they’re feeling confident as they prepare for Monday’s court case seeking Indigenous title to 200 square kilometres on Nootka Island, off Vancouver Island’s rugged west coast.

“I have absolutely no doubt that we will win because we believe in who we are,” says Archie Little, House speaker for the Nuchatlaht Tribe, which has about 150 members.

The claim covers provincial Crown land that contains Nuchatlitz Provincial Park at the northwest tip of the island, as well as lands granted as private forest tenures to companies such as Western Forest Products.

Band officials say a win would have enormous implications for the tribe, based at Oclucje, about a 20-minute drive west of Zeballos.

Success in court would give the First Nation the ability to manage and protect the land and resources. Band officials talk about protecting the trees and salmon while creating sustainable lives on the island.

Chief Jordan Michael believes it would give the nation tools to alleviate its housing shortage.

The nation filed a lawsuit in 2017 against the federal and provincial governments to gain title to the land. Forestry company Western Forest Products Inc., which has logged the area under provincial tenures, is also named as a defendant.

This case is the first application on the coast of the precedent-setting Tsilhqot’in decision in 2014, in which the Supreme Court of Canada for the first time recognized a First Nation’s title to a specific tract of land, said Nuchatlaht lawyer Jack Woodward, who was lead lawyer in the Tsilhqot’in case.

Observers will also be looking at the case in the context of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, which the province endorsed in legislation in late 2019.

Woodward says the Nuchatlaht were present when Capt. James Cook arrived on Vancouver Island in the 1700s.

“They’ve been there. They’ve always been there. What they are saying is that they would like to claim their legal rights,” said the Campbell River-based lawyer, who was among several speakers on a recent webinar offered through the B.C.-based environmental group Wilderness Committee outlining the significance of the case.

The province is arguing that the Nuchatlaht people abandoned their territory, but that is not the case, Woodward said.

“They were forced off their territory. … Their land was expropriated from them without compensation.”

Today, only about 20 per cent of the land claimed by the First Nation remains untouched by private logging, which resulted in the loss of culturally modified trees, he said. “This was a magnificent archaeological site” of world importance, Woodward said.

Remains of village sites with depressions where houses were located still exist, as do shell middens, he said.

A new study shows that forest gardens were created on the island where 17 types of trees and bushes were planted and cultivated, he said. “This was agriculture.”

Little said that Nuchatlaht people lived on the island for thousands of years. “We had no homelessness, we had nobody hungry, we had nobody out of work. We helped each other, we supported each other.”

When the Nuchatlaht lived on the island, its wealth was abundant, he said.

To Little, the island is “one of the most beautiful places in the world as far as I’m concerned.”

Success in the courtroom would mean the ability to “protect it better,” he said.

A rally is planned Monday morning outside the Vancouver courthouse where the eight-week case, with more than 180 documents, is scheduled to begin in B.C. Supreme Court.

In court documents, the province denies that the Nuchatlaht hold aboriginal title and asks the court to dismiss the claim.

Prior to the British Crown (and Spain in the late 1700s) asserting sovereignty over the area, the Nuchatlaht was a “relatively small and relatively weak affiliation of groups,” while other aboriginal people claimed and used lands and resources in the claim area, it argues.

Some of the Nuchatlaht’s assembly of localized family groups had been displaced from other areas outside the claim by other First Nations, according to the province.

It asserts that Nootka Island’s geography, such as steep hillsides, dense forests and rocky shorelines, limited the ability of the Nuchatlaht people to access and use the area. The Nuchatlaht depended largely on marine resources and used upland areas to a limited extent, it says.

The federal government denies that it and the province have infringed on or breached their constitutional duties regarding aboriginal title in the area claimed.

A Western Forest Products spokesperson said Friday the company would not comment, because the matter is before the court.