Picture a time before Simon Fraser University was built on top of Burnaby Mountain – before Burnaby Mountain was even a thing and powerful geological forces had yet to thrust the North Shore Mountains into existence.

In a subtropical prehistoric floodplain (where SFU now sits 370 metres above sea level), primeval trees and plants, including palms and sweetgum, dropped their leaves, flowers and pollen into the fine sediment of a shallow lake or pond.

There, they were compressed under layers of sediment for millions of years until one day when a young Rolf Mathewes was doing his undergraduate biology degree at SFU in 1967-68.

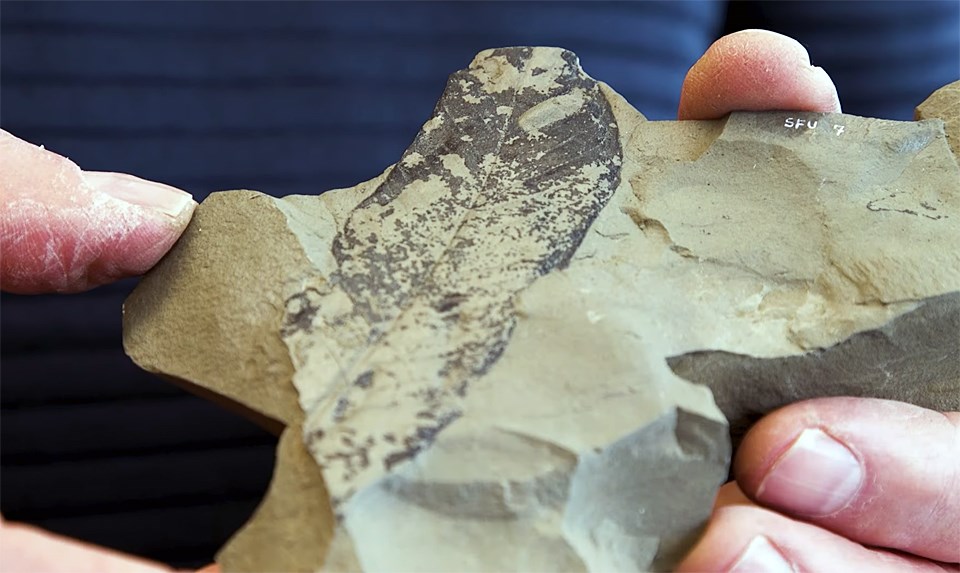

Construction at the fledgling university had uncovered a dark seam of shale sandwiched between the lighter sandstone and gravel that makes up most of the mountain’s bulk.

The seam caught the eye of biology professor Robert C. Brooke, and Mathewes, who was Brooke’s lab assistant at the time, was enlisted to help him sneak into the construction site after hours and collect samples.

“He noticed there were fossil leaves and bits on this grey shaley layer,” Mathewes said of his old professor.

They collected as many samples as they could (between 100 and 150) from spoil piles left behind by the excavators.

Neither Brooke nor Mathewes were fossil experts at the time, so the samples were locked into a cabinet marked “SFU fossils” for the next five decades.

Over the 50 years that followed, Mathewes built a distinguished career as a paleobotanist, specializing in microscopic fossils of prehistoric seeds and spores.

“I spend my time looking at the past through a microscope,” he said.

He returned to SFU in 1975 after a PhD at UBC and a post-doctoral fellowship at Cambridge University.

But for years, the fossils he collected in the 1960s stayed shut away.

“I knew what they were,” he said. “No one else would know, but I never unlocked the cabinet again because I was working on other things.”

About four years ago, however, Mathewes decided it was time to put the expertise he’d accumulated in the intervening years to work on the fossils he’d helped collect decades earlier.

Already in his early 70s, he figured it was time to tackle the project before he retired in earnest.

“I thought, really, you know, I helped collect these things, they’re right underneath our feet at SFU, I’m sure SFU would be interested in what’s under our feet and what it might be telling us about what the climate was like way back,” he said.

After examining the fossils on his own, he teamed up with Brandon University professor and palm fossil expert David R. Greenwood and University of Connecticut professor Tammo Reichgelt, who uses information about plant fossils to reconstruct prehistoric climates and ecosystems.

Their research was published in the latest volume of the International Journal of Plant Sciences.

What the team discovered, according to Mathewes, is that the SFU fossils date back about 40 million years to the late Eocene period.

And they reveal a very different kind of plant life from what we find atop Burnaby Mountain today.

There probably weren’t any conifers or needle leaf trees, for example.

Conifers would come to dominate the area much later before loggers cut them down at the turn of the 20th Century and then again in the 1940s, but Mathewes said he found no evidence of them among the SFU fossils.

What he did find was part of a fossilized palm leaf and other plant, seed and spore fossils that suggest the area was subtropical when they were laid down.

Reichgelt calculated the mean annual temperature where the SFU campus is now was 16.2 C – what you’d now find in modern day Wilmington, N.C. – and six degrees higher than the mean annual temperature at sea level in Metro Vancouver today.

The fossil collection Mathewes and his old professor spirited out of the SFU construction site 55 years ago wasn’t the largest or the most “beautiful,” according to Mathewes, but the pair’s efforts ended up preserving important material for the understanding of the mountain and the region 40 million years ago.

“There was enough there to make a complete story,” Mathewes said.

“Maybe I'll have a small part in advancing paleo-botany and paleo-climatology for that time period.”

He dedicated the research paper to Brooke’s memory.

Follow Cornelia Naylor on Twitter @CorNaylor

Email [email protected]