A local historian says time is running out to dig for lost history at a downtown Victoria construction site.

Kelly Black, a history professor at Vancouver Island University and executive director of the Point Ellice House museum, said construction of the 10-storey Telus Ocean building is an opportunity to search for treasures linked to the rich but little known history of Kanaka Row, a community of small seaside cabins named for the Hawaiians who lived there.

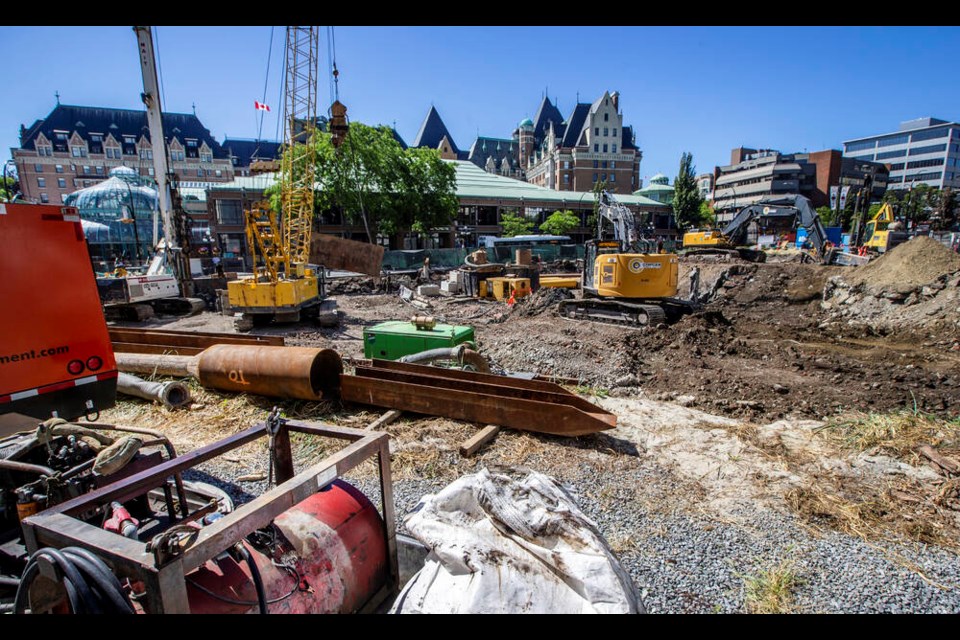

He said now, while the 28,000-square-foot lot east of the Empress Hotel is exposed in preparation for development, is likely the only time it will be possible to search for items linked to the community of Hawaiian, Indigenous, Chinese and European inhabitants and traders of roughly 170 years ago — before the artifacts are swallowed up by the development.

Under the site is the former James Bay mudflats, which have never been excavated for archaeological remnants, Black said. “There is potential, with the construction of this building, to learn more about this very diverse historical community.”

Telus said it has followed regulations and in 2019 engaged the provincial archaeological branch, which told them the site has low potential for archaeological findings.

“Although the risk was deemed to be low, we have implemented protocols in the event we encounter an archaeological find,” Telus spokesperson Lena Chen said in an email, adding that the corporation has engaged the Esquimalt First Nation and “assembled a team of archaeology monitors that will be present on site at all times throughout the excavation process.”

Telus said construction is in the early stages and to date no artifacts have been recovered.

But Black is skeptical of the process. The province’s Heritage Conservation Act regulates digging and excavating only on sites with artifacts, materials or physical evidence of human habitation that predate 1846.

Kanaka Row was established in the 1850s.

“The provincial requirements here are part of the problem,” Black said. “So if Telus is saying they met the requirements, that does not bode well for preserving the material history of Kanaka Row.”

“This has nothing to do with the construction or design of the Telus building," he added. "The construction of the building is actually an opportunity to learn more about this historical community.”

The B.C. Archaeology Branch said requests for inspection documents are backlogged and currently being processed into 2023. The department didn’t comment on concerns about the Douglas Street site, but said any sites with history post-1846 are handled by the B.C. Heritage Branch.

Raini Johnson, president of the Archaeological Society of B.C., said most Canadian provinces use a time period for archaeological regulations instead of a fixed date.

“It’s good for pre-contact sites,” she said. “But it really isn’t until the 1850s, when the Gold Rush happened, that we saw … settlers and people coming here to work such as Hawaiians, Chinese, Japanese people.

“The thing I dislike most about the 1846 date is that we aren’t protecting these marginalized communities’ histories,” she said. “History is basically taught through the lens of people in power, so we’re missing all this information from people who have had almost or as long of a history as white settlers in B.C.”

In the first half of the 19th century, many Hawaiians were hired to work across the Pacific Northwest at Hudson Bay Company trading posts. Around 1849, when the Colony of Vancouver Island was established, large numbers of Hawaiians began settling in what had become Fort Victoria, in an area along the north shore of xwsзyq’әm (pronounced whu-SEI-kum), the Lekwungen word for “place of mud,” which is now the lower causeway of the Inner Harbour.

Kanaka, according to Hawaiian open source library Ulukau, primarily means “human being” or “person” in Hawaiian.

Kanaka Row was established along expansive tidal mudflats, which were then full of clam beds and used by Lekwungen people as one end of a canoe portage during high seas.

The Fraser River Gold Rush of 1858 and expansive trading drew more people to the area, and Kanaka Row became one of many bustling B.C. communities of Hawaiians, First Nations, Chinese and European settlers. Intermarriage was common — Johnson said her grandmother was of Hawaiian and Tsleil Waututh ancestry.

“Our elders are passing away, and without heritage protection of these kinds of sites, we’re going to lose a lot of information,” she said.

Black said because Kanaka Row was on the water, it was frequented by visitors and traders from other First Nation communities, who likely used cabins in the area — mentioned in the writings of Emily Carr — while they visited.

“As Victoria grew, the people who lived there were displaced. [Kanaka Row] was removed for the creation of the Empress Hotel and other buildings,” Black said.

“A lot of these communities aren’t represented in the archival records the way white European settlers are represented in documents and objects. So there is a lot of potential here to learn more about people who didn’t leave as much and whose records weren’t valued as much.”

A City of Victoria self-guided heritage walking map exemplifies the disdain for the area, calling it a “hangout for cut-throats and thieves” where “knifings, fights and murders were common occurrences.”

People frequently came and went by boat, Black noted. Any number of objects may have been dropped or disposed of in the flats, which, in 1901, were filled in to construct the Empress Hotel, a national historic site since 1981.

Any site that is 500 to 1,000 metres within a shoreline is considered a high-potential archaeological area, Johnson said. “When we’re working with shorelines, there’s big potential of finding intact basketry, fish weirs and stuff like that.”

Black said the site could contain anything from china, bottles and pottery to carvings, pipes or even bones.

“There could be all kinds of objects,” he said, “but we don’t know until we look.”