KAMPALA, Uganda (AP) — Malaria season begins this month in a large part of Africa. No disease is deadlier on the continent, especially for children. But the Trump administration's decision to terminate 90% of USAID’s foreign aid contracts has local health officials warning of catastrophe in some of the world’s poorest communities.

Dr. Jimmy Opigo, who runs Uganda’s malaria control program, told The Associated Press that USAID stop-work orders issued in late January left him and others “focusing on disaster preparedness.” The U.S. is the top bilateral funder of anti-malaria efforts in Africa.

Anti-malarial medicines and insecticide-treated bed nets to help control the mosquito-borne disease are “like our groceries,” Opigo said. “There’s got to be continuous supply.”

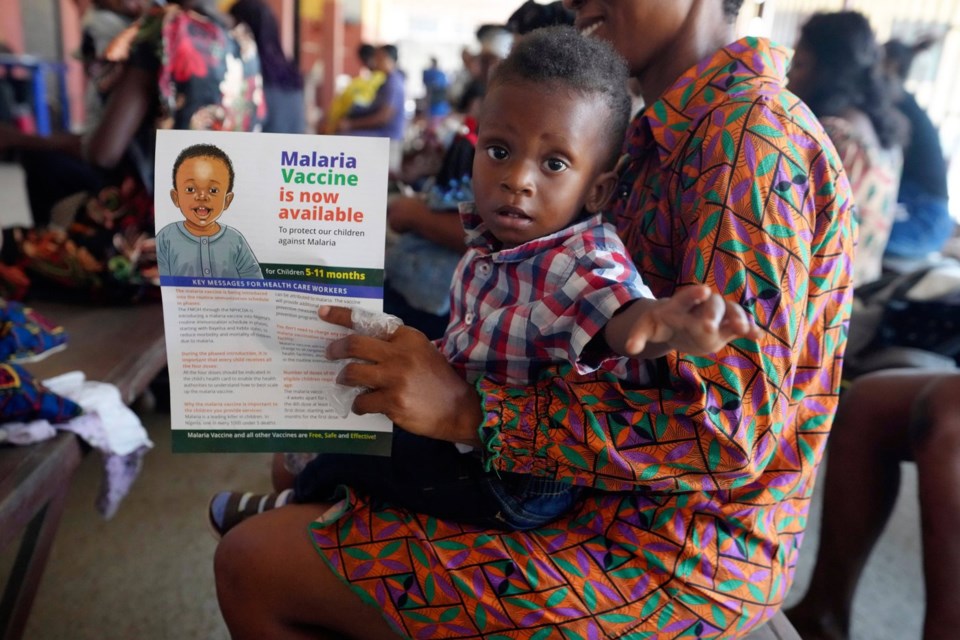

As those dwindle with the U.S.-terminated contracts, he expects a rise in cases later this year of severe malaria, which includes problems like organ failure. There is no cure. Vaccines being rolled out in parts of Africa are imperfect but are expected to largely continue with the support of a global vaccine alliance.

The Washington-based Malaria No More says new modeling shows that just a year of disruption in the malaria-control supply chain would lead to nearly 15 million additional cases and 107,000 additional deaths globally. It has urged the Trump administration to “restart these life-saving programs before outbreaks get out of hand.”

Africa's 1.5 billion people accounted for 95% of an estimated 597,000 malaria deaths worldwide in 2023, according to the World Health Organization.

Health workers in the three African nations most burdened by malaria — Nigeria, Congo and Uganda — described a cascade of effects with the end of most U.S. government support.

The U.S. has provided hundreds of millions of dollars every year to the three countries alone through the USAID-led President’s Malaria Initiative.

The U.S. funding has often been channeled through a web of non-governmental organizations, medical charities and faith-based organizations in projects that made malaria prevention and treatment more accessible, even free, especially for rural communities.

Uganda in 2023 had 12.6 million malaria cases and nearly 16,000 deaths, many of them children under 5 and pregnant women, according to WHO.

Opigo said the U.S. has been giving between $30 million and $35 million annually for malaria control. He didn't say which contracts have been terminated but noted that field research was also affected.

Some of the USAID funding in Uganda paid for mosquito-spraying operations in remote areas. Those operations were supposed to begin in February ahead of the rainy season, when stagnant water becomes breeding ground for the wide-ranging anopheles mosquito. They have been suspended.

“We have to spray the houses before the rains, when the mosquitoes come to multiply,” Opigo said.

Already, long lines of malaria patients can be seen outside clinics in many areas every year. Malaria accounts for 30% to 50% of outpatient visits to health facilities across the country, according to Uganda National Institute of Public Health.

Nigeria and Congo

Nigeria records a quarter of the world's malaria cases. But authorities have reduced malaria-related deaths there by 55% since 2000 with the support of the U.S. and others.

That support is part of the $600 million in health assistance the west African country received from the U.S. in 2023, according to U.S. Embassy figures. It was not immediately clear whether all of that funding has stopped.

The President’s Malaria Initiative has supported Nigeria’s malaria response with nearly 164 million fast-acting medicines, 83 million insecticide-treated bed nets, over 100 million rapid diagnostic tests, 22 million preventive treatments in pregnancy and insecticide for 121,000 homes since 2011, the embassy says.

In Congo, U.S government funding has contributed about $650 million towards malaria control since 2010.

Now, some of the successes in fighting malaria in Congo are being threatened, which will complicate already difficult efforts to identify and track disease outbreaks across the vast country as supplies and expertise for malaria testing are affected.

Worsening conflict in Congo's east, where some health workers have fled, has raised the risk of infection, with little backup coming.

With the loss of substantial U.S. support, “a lot of people are going to be affected. Some people are really poor and cannot afford (malaria treatment),” said Dr. Yetunde Ayo-Oyalowo, a Nigerian who runs the Market Doctors nonprofit providing affordable local healthcare services.

Up to 40% of her organization's clients are diagnosed with malaria, Ayo-Oyalowo said.

There is hope among health workers in Africa that, even after the dismantling of USAID, some U.S. funding will continue flowing via other groups including the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. But that group also received U.S. support and has not issued a public statement on the dramatic cuts in U.S. aid.

Opigo in Uganda said the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health might be sources of help.

But he added: “We need to manage the relationship with the U.S. very carefully."

___

Asadu reported from Abuja, Nigeria. AP journalist Dan Ikpoyi in Lagos, Nigeria contributed.

Rodney Muhumuza And Chinedu Asadu, The Associated Press