Once skies clear after a snowstorm, patrollers have thrown all the bombs, and alpine lifts start spinning, there’s arguably no better place to be in the Sea to Sky than in line for Whistler’s Peak Express.

That’s not just because Peak Chair is the gateway to some of the best lift-accessed terrain on the continent. Good skiing aside, it’s where you can usually witness one of Whistler’s favourite powder day rituals. At least, you could before Whistler Mountain closed for the season on April 16.

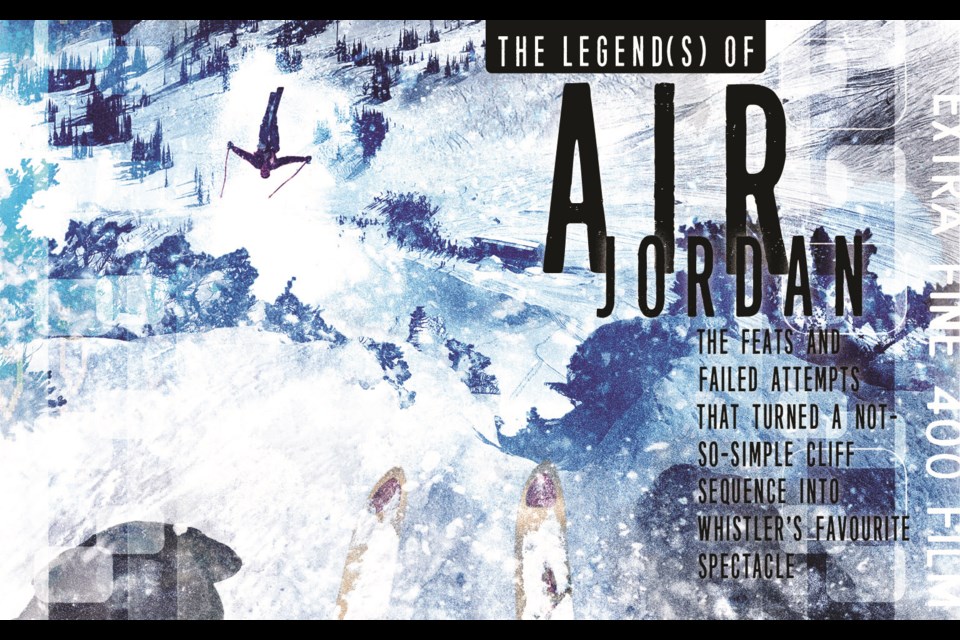

It all begins when the first Gore-Tex-clad figure appears on top of a ridge to looker’s right of the lift, lined up above a steep, jagged cliff face. Murmurs start and heads swivel. Anticipation grows as that person takes a deep breath, and, as a chorus of hollers and ski-pole taps rings out from the lift line, launches themselves over the edge.

You won’t see it listed next to a pair of black diamonds on Whistler Blackcomb’s official trail maps, but the terrain has a name: Air Jordan.

The specs

The famous feature consists of two consecutive cliffs, starting with an approximately 4.5-metre (15-foot) step down. It wouldn’t be particularly impressive on its own, by Whistler standards, but upping the ante is the steep patch of snow underneath, where riders usually have about six metres of runway to get their bearings on the 47-degree slope before sending it over the main event: an approximately 18-m cliff.

An optional drop near the bottom of the slope, called the third step, rounds out the cliff sequence.

Underneath and to skier’s right of Air Jordan are the almost-as-impressive, 12-metre Waterfall cliffs.

Air Jordan’s magic stems more from its location than its considerable difficulty. Directly in view of Peak Chair, a good snow day usually means a captive audience of hundreds collectively losing their minds as skier after skier drops into the amphitheatre. These days, Air Jordan’s audience extends far beyond the lift line, as cellphone footage of stomped runs and big crashes inevitably makes its way to social media.

It’s a unique combination of factors that has created “one of the biggest spectacles in skiing,” says pro freeskier, filmmaker and perennial Favourite Whistlerite Mike Douglas.

With the hyped-up crowd, “it’s a bit more of a Hollywood cliff,” says pro freeskier, backflip specialist and former World Cup ski-cross athlete Stan Rey. “There are definitely better cliffs with better landings on the mountain, but it is kind of a staple in Whistler.

“All the freeride kids … want to hit Air Jordan. That’s what they work up to.”

That’s true, confirms 18-year-old Whistler Freeride Club alum Marcus Goguen. “Growing up in Whistler, looking at it every day since I was six, watching people hit it, lining up for Peak Chair and just the vibe of everything, it definitely made it a goal of mine,” he says.

The crowd “adds a lot more stoke” to the experience, says Goguen, but it also makes it near impossible to chicken out.

“If you get there and it’s not great, you’re almost fully committed once those people see you on top of Jordan and you hear them cheering. There’s no backing out,” he says with a laugh. There is, however, “a lot of shame in climbing back up,” he adds.

The best part? “Every powder day, being in the Peak Chair lineup and watching [the show], everybody’s a part of it, whether you’re skiing it or just watching,” says Goguen. “That’s the cool aspect of it.”

Humble beginnings

Yes, the feature shares a name with Nike’s iconic sneaker line, created in the ’80s for a particularly legendary Hall of Fame NBA player. For sure, riders launching themselves over the cliffs do get more airtime than Michael Jordan dunking a basketball. But that’s not how the line earned its moniker.

It’s named after Jordan Williams, a longtime Whistler Mountain Ski Club coach who graduated to Alpine Canada’s ski-cross program six years ago. Legend has it Williams was first to descend the cliffs, on a pair of skinny race skis in the mid-’80s.

Specifically, it was in 1986, on a pair of 210-centimetre GS planks, he confirms.

“I’d been looking at doing that since I was about 12 years old, riding the old Red Chair,” he says.

That was about a decade before he found himself on top of the line he’d spent years mapping out in his mind. It was Williams’ second year coaching, and his first since retiring from ski racing, which meant more time for freeskiing before shifts at Citta’s. A film crew was in town, according to Williams’ friend Steve Miller. Did Williams want to ski? “I said ‘Sure, why not?’” Williams recalls. “It was a day off.”

Williams was more concerned about skiing the feature than airing it. His plan was three turns in, three turns on, three turns out. “The first time I did it, I screwed up on that,” he says.

Williams’ second turn on the second pitch took him further right than he hoped. “I didn’t land clean,” he says.

He ended up climbing out, still high enough on the slope to traverse skier’s right for some redemption. “I was so mad that I didn’t [land] it well that I went a little too hot off the Waterfall and almost hit flat,” he says. “That was pretty heavy. I just remember my goggles were on and then when I stood up, my goggles were on my forehead. I’m just glad my knee went beside my head instead of into it.”

A couple of days later, Williams grabbed his 205-cm slalom skis and headed back uphill to try again. “It worked way better,” he says. “I got it done the way I wanted to. I felt that I’d accomplished that bit of a thing I’d been looking at forever.”

About a year passed before Williams’ buddies started referring to the cliffs as Air Jordan. The name caught on, and stuck.

So much so that, years later, after friends named their sons after Williams, those Jordans (Chew and Ling, respectively) came to him asking for permission to hit the cliff themselves. “It was kind of like a namesake for them that they felt they had to achieve,” says Williams. “I hope no one hurts themselves because they feel they need to do it, just because they got that name. But it was kind of a neat little thing attached to it.”

It’s “really nice having those connections with such good skiers that always challenged themselves,” he adds.

Williams’ first drop took place around the same time a teenaged Douglas started making trips to the resort from Vancouver Island, and the same year Whistler installed the first Peak Chair, a 1,000-metre-long triple chairlift.

“I remember hitting some of those cliffs, as well,” Douglas says. “People would talk about that whole Waterfall area, like, ‘That guy went and hit that cliff two months ago.’ These weren’t things that got done all the time, they just got done once in a while by what were viewed as pretty crazy people—which was me when I was 16, for sure.”

Peak Chair changed the game in terms of providing easy access to those cliffs and the rest of Whistler’s high alpine, but that nearly wasn’t the case. “The original plans for the Peak Chair were that it was just going to go to the first bump,” not the summit, Douglas explains. “They thought it was too aggressive to put people up there, over those big cliffs.”

Until Whistler officials learned their rivals over on Blackcomb were installing a T-bar to the top of 7th Heaven in 1985. “They quickly redrew the plans and said, ‘Well, they’ve gone to the top, so we have to go to the top,’” says Douglas. “Which was a blessing, because they would have just had to rip that thing out and put it to the top anyways.”

According to Douglas, it wasn’t until the late-’90s or early-’00s—when freeskiing and big-mountain snowboarding started taking off—that powder days became a race for features like Air Jordan.

“It became, ‘You’ve got to get there and you’ve got to get there first, otherwise you’re going to have tracks,’” he says.

In those days, as a member of the Whistler Mountain Ski Club, Rey spent more time between gates than dropping cliffs. Still, every once in a while, his coaches—including Williams—would let their charges loose to enjoy a fresh snowfall away from the groomers.

It was on one of those occasions when Rey learned the double cliff he’d been eyeing wasn’t, in fact, named after a basketball player. Rey still remembers Williams’ response when he told his coach how much he’d love to hit Air Jordan while the pair were freeskiing. “He’s like ‘Ah, I hit that all the time, it’s named after me,’” Rey recalls.

“I thought he was joking at first,” he adds. “And he wasn’t.”

Rey already had plenty of respect for his coach, but this particular distinction “made him seem a little bit more of a badass,” he admits.

Still, Williams insists he deserves “no recognition, claim to fame or anything.”

Timing and Williams’ progress on skis just happened to line up. “We just skied off that sucker, and then my friends started doing it … and then next thing you know, a lot of people were giving it a shot,” he says.

The feats

It took a few years, but Rey eventually found himself standing on top of the cliffs for the first time in March 2013.

The Whistlerite’s Air Jordan debut coincided with what’s still widely considered the most iconic stunt ever thrown off the feature, even a decade later.

Rey skied the line alongside world record-holding cliff-jumper and big-mountain skier Julian Carr, who that day decided to ignore the landing pad in between steps. With blue skies above and 120 cm of untracked snow below, Carr launched over the entire feature to land what ended up being a more-than-55-m (or 185-ft) jump. He also laid out a swan-divey front flip, just for fun. Underneath, Rey sent it off Jordan the usual way, tossing in a backflip off the second step, while a crew of extras made their way down the surrounding slope. The feat was captured by Whistler’s Sherpas Cinema for its iconic 2013 ski film, Into The Mind.

“A few times I’ve been up to Whistler I’ve glanced at the idea from the back of my mind—the kind of glance that is fleeting and more of a brief fantasy than a real idea,” Utah-born Carr told Pique’s Andrew Mitchell in 2013, shortly after the jump. “The idea came about a week ago when Stan Rey mentioned there was a beautiful platform up there and I could send the whole thing from it. Stan mentioned it fleetingly as well; I don’t think he knew that I was listening intently!”

At the time, Carr called it his “rowdiest move to date.”

Carr’s clearing all of Air Jordan in one go might be the best-known attempt, but it wasn’t the first. That title apparently belongs to the late Dave Treadway, the pro skier who passed away in the Pemberton backcountry in April 2019.

Treadway “was the first that I am aware of that single-staged Air Jordan,” says Douglas. “It wasn’t for a big film shoot or anything, so I think it’s something lots of people don’t know.”

As Rey remembers it, the feature “is pretty intimidating, especially on your first time. It’s a fairly steep shelf and then the second drop, depending on the year, can be fairly big and the landing is kind of flat.” Still, during the March 2013 Sherpas shoot, “I was more scared for Julian Carr than I was for myself, because what he was doing was pretty insane.”

The backflip “probably wasn’t the best thing to try and do” on his first time off Jordan, Rey admits with a laugh. “I landed pretty far back … but it ended up working because the shot was so wide.”

Rey’s second Air Jordan attempt—and every attempt since—was for another film project, Whistler Blackcomb’s Magnetic in 2017. It was the first full-length ski and snowboard movie filmed entirely within a single resort. In his clip, Rey skis an action-packed, top-to-bottom Whistler lap that includes a 360 off Air Jordan and an enormous double-backflip off the third step.

“I did it the first time and I thought I did it pretty good, but my filmer Jeff Thomas thought I could do it better. So, I went up and did it again and again—not in the same day, but I think I hit it six times for Magnetic.” (The footage used in the final cut was from Rey’s first run.)

Jordan’s Next Gen

“It’s actually kind of funny that I’ve only hit Jordan when filming—I’ve never hit it on my own,” says Rey.

And he doesn’t plan to. At 35, Rey’s getting older, and Jordan’s landing isn’t getting any softer. Instead, he’s leaving it to the next generation of Whistler freeriders, like Goguen.

Two years ago, footage of the then-16-year-old Whistler Freeride Club athlete hucking Jordan made its way around the internet before it was eventually posted by skiing forum Newschoolers. The video shows Goguen sending a mind- blowing, massive backflip off Jordan’s main cliff and a just-as-huge second backflip off the third step, capped off with an exceptionally filthy landing. It won clip of the year in Newschoolers’ Best of 2021 contest.

“It was definitely a steppingstone in my career, that clip,” says Goguen.

The 18-year-old won the Freeride Junior World Championships this past January before taking second place in his Freeride World Tour (FWT) debut one month later. He finished the FWT season in ninth to become the top-ranked Canadian man on tour.

The backstory behind the clip makes Goguen’s backflip-to-backflip sequence even more impressive. “I was actually coming up from school, after an exam,” he remembers. “It was midday, and I rushed up because I saw it was firing on the mountain. I still decided to go to Jordan after, I think, like 10 or 15 people had hit it.”

Snow conditions on the landing were “absolutely terrible,” Goguen recalls. “But I was a young, stupid kid—I still am—so I decided to go for it.”

He’s glad he did, but he probably wouldn’t make the same decision in the same conditions today. Goguen estimates it was one of five or six times he’s skied down Air Jordan since first dropping into the famous cliffs when he was still in elementary school. “I was probably 10 or 11,” he says. That could very well make Goguen the youngest skier to drop into Jordan, but he can’t say for sure.

For many skiers, the feature is “sort of a rite of passage,” as Goguen describes it. “It’s a way to prove yourself in the freeride industry, and just locally, mostly.”

That rite of passage’s namesake says he’s “amazed” by every line he’s seen Goguen stomp on the feature.

“They’re always very creative and landed perfect, just in time,” says Williams, adding, “It’s beautiful to watch what he can do and how well he can do it.”

Still, Goguen isn’t done pushing the limits of what’s possible on Jordan. “I definitely have a couple more tricks I want to cross off on it,” he says.

That might include a 360 off the first step on a super-deep powder day, or the same high-flying Cork 720 his buddy Jérémie Paquette’s been attempting to land off the second step this winter. Or maybe Goguen will throw that trick off the third step instead.

A Cork 720—an off-axis spin with two full rotations—off the last cliff “is actually what I was aiming to do when I did that first backflip-to-backflip run, but just in the moment decided to hit a backflip instead,” Goguen says.

To Douglas, the ultimate Jordan attempt would include tricking all three drops. “I don’t think it’s been done yet,” he says.

Goguen has two out of the three down, but “it is very, very difficult to do a trick on the way into the upper step of Air Jordan, because of the weird takeoff,” Douglas adds.

But the freeskiing legend says he wouldn’t put it past the younger generation.

“They seem to do things that I say, ‘Oh, no, you can’t do that,’ and they’re like, ‘OK, watch this.’”

The fails

Most of the time, for Rey, “the bails are more entertaining” than the clean landings. “There’s so much carnage on there,” he says. “I’ve seen people lose skis, drop poles up there, and they get stuck on the shelf.”

Usually, those skiers will need to head back to Jordan another day to retrieve their equipment. Usually. In his first of six attempts skiing the line for Magnetic, Rey did one unknown skier a favour after hitting a ski buried on that shelf, knocking it down as he launched into a 360.

“It fell off the cliff behind me. I didn’t really notice it—I thought I tagged a rock—but then there was a rumour that I did, like, a hand-drag three and grabbed that ski and threw it off while I was doing the 360,” Rey laughs. “Which is a complete lie.”

Some falls, like the one then-18-year-old Jaden Legate suffered last April during his first-ever attempt dropping Jordan, are even more memorable than the successful runs. The hundreds of people in line for Peak Chair that day watched as the lifelong Whistler local hucked himself off the first step, double-ejected out of his skis, and ran forward off the second step, not unlike a stuntman jumping out of a building, engulfed in flames. The crowd’s concern turned to cheers when Legate, luckily, emerged from the tumble unscathed. Footage of the fall went viral, even landing a spot on @jerryoftheday’s Instagram feed.

“I could tell that the landing was pretty firm when I was going to go, and I kind of went for it anyways, so that may have played a factor in why I fell,” Legate told Pique last year following his brush with internet fame.

“If you’re not fully confident, don’t do it and just wait for the right conditions, because you can always wait,” he added wisely. “It’s not worth risking your life over; it’s just a cliff.”

Rarely, the spectacle can turn from ski film to horror movie in an instant. That was the case in February, when a friend of Goguen’s crashed off the cliff and landed on exposed rocks. The fall earned the local teenager a broken back and a helicopter ride off the slopes.

“It was not a good scene,” Goguen recalls. But there is good news: the skier healed “super quick,” and, as of April, was already back on snow.

The key to avoiding those falls “is to land balanced off the first step,” says Douglas. “The mistakes I most often see is people don’t land the first step well, and then they’re in a bad position as they take off the second step and then they end up floundering.”

Fortunately, “there’s definitely a lot worse [landings] out there” than Air Jordan’s, Douglas adds. “The fall ratio on it is pretty high, but the injury ratio on it seems to be pretty low.”

What about the boarders?

Snowboarders don’t have to worry about leaving their equipment behind the same way skiers do, but the qualities that make Air Jordan challenging to land with four edges make it even more difficult for riders operating on two.

It’s why boarders don’t hit Air Jordan nearly as often as skiers, Douglas reasons. “In the early 2000s, late-’90s, there were some snowboarders who did some pretty cool stuff on the Waterfall just below there—Greg Daniels and Matt Domanski come to mind—but I think it’s just that you’ve got to kind of land on edge, and that’s trickier on a snowboard,” he says. “Especially if you’re not the first one in there.”

Working with one edge “makes it almost impossible to stop or even slow yourself down enough to change direction or set a different line—you have to really commit to jumping straight,” agrees Whistler snowboarder Jay Baumann.

A local named Rich Carlson claims to be the first-ever snowboarder to drop into Jordan, but Baumann is among just a handful to hit it within the last few years. He’s made five attempts in the decade he’s called Whistler home, three of which he counts as successful.

Baumann, who volunteers as a coach with the Indigenous Sport Life Academy, started directing more energy towards big-mountain riding as he transitioned out of freestyle snowboarding after the pandemic. Last winter, he ranked 10th in Canada in the FWT qualifiers.

Baumann says he only knows of two other snowboarders who have ridden Jordan in the last three or four years—both “just got washed over the cliff,” he says—but he’s watched enough skiers stomp the landing that the feature became as much of a rite of passage for him as it is for freeskiers like Goguen. “I [thought], ‘If the skiers could do it, I can do it as well,’” he says.

“You can’t really say you’ve done it all until you’ve checked off Air Jordan successfully. I think it’s nice to have something that brings together a lot of the locals that are left, because everyone knows that it’s always that grand show at Peak Chair. It’s nice to still have those little things that bring everyone together and still have that true ski-bum soul that used to be running rampant in Whistler.”

Baumann filmed a couple of those Jordan drops and posted the footage to TikTok earlier this year. In one P.O.V. clip that has so far garnered more than 330,000 views, Baumann hits a rock on the landing pad, but manages to regroup before launching off the second cliff, landing on his feet and riding out.

“I feel like freeride doesn’t really get the same amount of exposure as park riding does,” says Baumann. “There’s a lot of videos out there of people riding these gnarly lines on skis, so I thought it would be good to put out a bit of inspiration for other snowboarders out there, to show that it is possible for us to do the same things.”

His tips for any other boarders looking to put their skills to the test on Whistler’s biggest stage? Work up to the feature by riding more intense terrain around the resort. “Making sure you can ride all of the Waterfalls, from all of the different angles, is a good one,” he says. “Anything that has a mandatory air is good practice.”

Then, when you’re ready, “Make sure you’re one of the first people to hit it and just commit to it 110 per cent,” he adds. “Hang on, because it’s a bit of a wild ride until you get to the bottom.”

@theefrother The hype up is real #whistlerairjordan #freeridesnowboarding #thisisfreeride #ejackknife #whistlerblackcomb #604 ♬ Oh my God. - Quinny👍