Hundreds of people made their way through the building to eat and pray over the course of the full moon celebration last week. The night was still and clear as vehicles arrived and departed, carrying people to and from the temple. The golden adornments atop the building caught and reflected the moonlight. Inside it was noisy as groups of people made their way through the dining hall, filling their trays with food and chatting over their meals. Upstairs was loud too, as the sounds of devotional singing echoed in the main chamber.

Downstairs at one of a dozen long tables in the dining hall, or langar, a family of four were enjoying some supper before heading up for prayer. In between mouthfuls of dal, chapati, and rice pudding, Gurmeet Marok explained why he comes here regularly.

“This is a part of living,” he said. “We go at least once a week to go to the temple for prayer and to be in touch with our belief.”

He consulted his partner, Ravnat, and tended to his children before continuing the conversation.

“The best thing about this religion is you don't have to be religious,” he added. “Anybody is welcome regardless of cast or colour. That is what it's about. You don't have to be a proper Sikh. Anybody can come and join, anybody can pray.”

The Maroks bought a business here and moved from Prince George in 2012. The Sikh Temple is where they come to be part of the community and fulfill the religious aspects of their lives.

Gurmeet and his family are seated among the young and the old, the devout and the religiously disinterested, skateboarders and climbers from Ontario, Squamish's can collectors, Hindu, Christians and Sikh.

As is the custom in langars around the world, this Sikh Temple serves simple, vegetarian meals for free in order to accommodate a wide variety of dietary requirements and to prevent any one congregation from using upscale food as a symbol of wealth.

This purposeful openness to diversity and efforts to help those in need exists in many aspects of life at the temple. Helping needy people without any distinction of background, race, or even religious belief is a central tenant of Sikhism. Followers of the faith are expected to contribute at least ten per cent of their wealth or income to needy people. Every day of the year, the temple is open to people who need something to eat or a place to stay. So long as they don't smoke or drink in the temple and aren't obscene or disruptive.

“Anybody is welcome, at any time. If anything else is going on in the community and you ask the Sikh community to come forward and help you they will definitely go, no matter who it is,” said Gurmeet.

Avtar Gidda is the secretary of the Sikh Society. He elaborated on the Sikh's philosophy of helping people who are in need.

“People are supposed to be happy, they are supposed to not be fighting, they're supposed to be coming and sharing their ideas. If there is any kind of problem, they're supposed to solve it as a human being,” he said. “Sometimes there is a problem with the neighbours and we go in and we say, we don't want to fight, or we don't want to bring a bad name to the society or to the neighbourhood. That's why the Squamish Sikh Society is very much established and peace loving. We have no quarrels in either the school, nor in the work place.”

The night of the full moon was a little bit busier than the typical evening around the temple, as the first day of the lunar month holds a particular significance in the religion.

Makhan Sanghara, president of the Squamish Sikh Society, explained that the full moon, or Kartik Poornima, is a time of rejuvenation.

“We celebrate the full moon for the change of the cycle of the atmosphere,” he said.

The Kartik Poornima is also an important day for Sikhism because the founder of the faith, Guru Nanak, was born when the moon was full. Nanak travelled widely in India, China and the Middle East. He collected scriptures from various faiths including Islam and Hinduism.

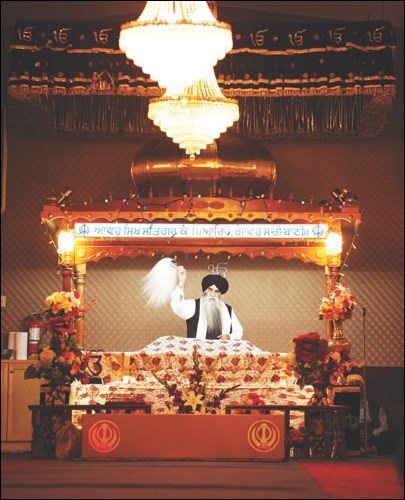

Nanak's ideas, along with those of subsequent gurus, are now incorporated into the central text of the religion, the Adi Granth. The 1430-page book is written in dialects of Punjabi, Sanskrit and Persian. A copy exists in every Sikh Temple and is kept on a decorated platform at the front of the main hall, behind which sits the priest.

Next month, the Temple will commemorate Guru Nanak's birthday by holding 48 consecutive hours of prayer. The Adi Granth will be read aloud in its entirety as groups of five or six people at a time take two-hour shifts reading.

The text is read aloud during Kartik Poornima as well. Heading up the stairs to the main hall, or Darbar, devotional singing can be heard from above. Inside, the well-lit room, the priest reads short orations from the Adi Granth and the assembly who are seated or kneeling on the floor respond in unison.

Sikh and other Indo-Canadians lived in Squamish for over a quarter of century before the temple was built. Many Sikh men first came to work in the logging industry at the beginning of the 1900s. At first it was just men who stayed in camps and whose families usually resided in Vancouver.

Then with the completion of the highway to Vancouver in 1958 and the opening of a new sawmill by Weldwood in 1962, there was an influx of people moving to Squamish. As Squamish grew, so too did the number of Indo-Canadians and particularly the Sikhs. The first family to move here were the Mahngers in1964, followed closely by the Ozlas. Their descendants continue to reside in Squamish.

Employment for Sikhs during the seventies was primarily at the saw mill, but some men began working at B.C. Rail. A few of the young women worked in the pharmacies and banks. The majority of the families lived either downtown or in Valleycliffe, but some bought houses in Brackendale and Garibaldi Highlands.

Avtar Gidda who moved to Squamish in 1969, recalled these early days before the temple.

“We have religious needs and we have to go to Vancouver. That was a long trip at the time because the road wasn't very good.”

Gidda noted that in the early 1970s there were about 150 Indo-Canadians working in the Weldwood saw mill.

In August 1980, the Squamish Sikh Society was incorporated. The need for a place of community in which to fulfill religious needs culminated with the construction of the temple – completed in March 1983.

The temple has remained largely unchanged over the years. In 2004, an additional eating room off of the langar was added. Sikhs who follow a more traditional practice often prefer to be seated on the floor for eating.

“We don't want to fight and have people feel disgusting and that's why we changed this that way,” said Gidda.

In 2009, the kitchen was renovated and a lift was installed for people with mobility difficulties to move between the langar and the darbar.

Portables behind the temple now serve as a school for which there are three teachers and about 75 students. Punjabi, English and religious education are the subjects here.

Though the building is tucked away on fifth avenue and the temple's patrons seem to maintain a quiet disposition around town, the Sikhs represent a substantial component of Squamish's population, culture and history.

Five hundred families, some 1,500-1,600 people spanning 27 nationalities now frequent the temple for prayer, education and community. Many of the Sikhs who regularly attend the temple live in Squamish and work here, or in Whistler or Vancouver.

For governance, the temple has volunteers who fill the roles of president, vice president, secretary, vice secretary and treasurer. These positions are voluntary and, if required, are changed at a general meeting held each year between Christmas and New Year.

Back in the langar, Kirin Taylor and a few of his friends are finishing up their supper. They're visiting Squamish for a couple of weeks from Owensound, Ontario to check out the town and to go skateboarding and biking. Taylor was quite pleased about being able to come here for free supper.

“All I can say is that it's awesome food. It's a pretty cool scene,” Taylor said. “Good people and good food… you can't ask for much more.”

Today (Thursday, Oct. 23) a celebration of Dwali, or the festival of lights, is being held at the temple. In essence, it marks the victory of light over darkness and involves elaborate clothing, decorations, and festivities at Gurdwaras around the world.