For Saplek AKA Bob Baker, a Skwxwú7mesh Elder, the signs of colonialism are always present, but he is encouraging other First Nations to “step on it” to keep it from recurring in the future.

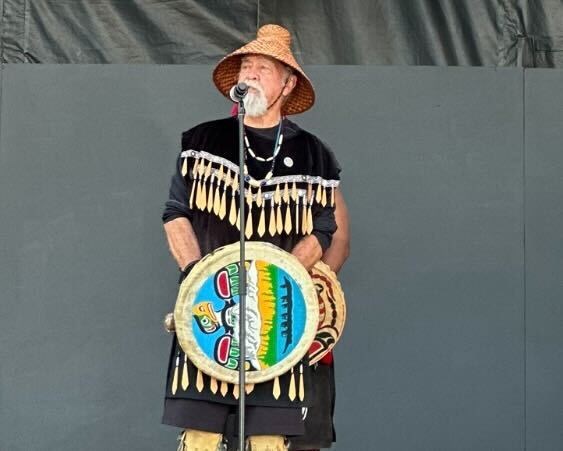

Baker, known by his Skwxwú7mesh name Saplek and Hawaiian name Lanakila, recently shared his journey and reflections on Indigenous culture during an interview with The Squamish Chief after his performance at the Tatus Festival on Aug. 30, held at the PNE Fairgrounds.

The festival, named after the Nuu-Chah-Nulth word for "star," was organized by Canoe Cultures to celebrate Indigenous music, arts, and culture. With over 700,000 visitors attending the PNE Fair annually, the festival offered a significant platform for highlighting Indigenous traditions to a broad audience.

Early Memories and Identity

Reflecting on his childhood, Saplek remembered the challenges he faced while attending St. Paul’s residential school. “I was six years old when I went into St. Paul School. I can still remember the feeling of being abandoned, something I had never experienced before. I thought someone was going to come back and get me, but after a while, I realized I was on my own.”

He explained how this experience shaped his identity, stating, “Saplek is better. Bob Baker is a colonized name.”

The residential school system, which operated in Canada from the 1870s until 1996, saw over 150,000 Indigenous children forcibly removed from their families. Many, like Baker, endured physical and emotional trauma. An estimated 6,000 children died at residential schools, though records are incomplete.

Cultural Advocacy and the Revival of Tradition

Saplek’s commitment to cultural advocacy began in 1990 with the creation of the first ocean-going canoe for the Skwxwú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish Nation). His respect for tradition and protocol has guided his work ever since.

“When I leave a nation with our canoe, I usually leave seat number two open for at least half an hour. As we leave the territory, I tell the hosts that we are leaving that seat open for the ancestors of that territory to travel with us—a gesture of appreciation and respect.”

In 1994, Baker co-founded Spakwus Slolem, a dance group that quickly gained international recognition.

“We came up with the name 'Spakwus Slolem' in 1994. Because of how we put our presentation together, we were invited to the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland. We had a leather shop in Geneva that sponsored our time there—they called the owner 'Cowboy Bob' over there. We were hired to open the stage for a Western act called Buck Owens.”

Spakwus Slolem, also known as the Eagle Song Dancers, represents the Nation. The group highlights the rich traditions of the Skwxwú7mesh people, including their canoe culture, through songs, drumming, dance, and audience participation. They have performed in various countries, including Taiwan, Japan, and Switzerland, promoting Indigenous culture on a global scale.

Lessons from the Past

Baker’s dedication to preserving Skwxwú7mesh traditions is deeply rooted in the teachings of his father. “My dad was a chief and a language teacher, a very traditional person. He was deeply involved in hunting, fishing, and doing things for the people, like working with canoes and gathering wood for various celebrations. He taught me about protocol and where to look spiritually and mentally—how to present who we are through our actions, words, songs, and intentions.”

However, Baker’s time in residential school made it difficult to maintain his language and culture. "The cultural part was starting to come back, but the language—we weren't allowed to speak it. We were not allowed to talk (about) it. So, I had very little exposure to our language, only during the summertime or winter breaks when I was around my parents."

Despite these hardships, Baker now sees a revival of the language and culture in his community. "Nowadays, it's full immersion—everyone's in the language now. I am learning from my nieces and nephews who are fluent, and we have immersion schools. I’ve been involved with that as well."

Language revitalization efforts have been crucial in preserving the Skwxwú7mesh language. According to the First Peoples’ Cultural Council, there are approximately 4,700 speakers of the Skwxwú7mesh language, a significant increase from previous decades, thanks to community-led initiatives.

Marching Toward Reconciliation

Reflecting on his time at residential school, Baker shared, “The last two years I was in Kamloops, we formed a marching band. They gave us porcupine roaches and headdresses, and we did a lot of beadwork. We performed at rodeos in Kamloops, Williams Lake, and other places. That was my introduction to being in the public eye, and it was uncomfortable, but I thought it was pretty good.”

As the conversation turned toward the present, Baker highlighted the ongoing challenges posed by colonialism. "The big question nowadays is about colonialism—how it's defined and how to prevent it from happening again,” he said.

“We see the signs of colonialism all around us, in our names, in the way we were ordered to live. It tries to rear its ugly head every once in a while, but every time it does, we have to step on it and keep it from recurring."

Baker is deeply involved in the reconciliation process, particularly in the West Vancouver School District, where he works to educate youth about local history, residential schools, and the deeds of local warriors. “Reconciliation is an ongoing process. They say it will take seven generations to realize full reconciliation.”

Bhagyashree Chatterjee is The Squamish Chief’s Indigenous affairs reporter. This reporting beat is made possible by the Local Journalism Initiative.