New research from a Vancouver laboratory has found setting your washing machine to its gentle wash cycle can lower the shedding of microscopic plastic particles by 70 per cent.

In a report released Tuesday, nearly two dozen researchers and technical experts came together from Patagonia, Samsung and Ocean Wise to assess how synthetic clothing sheds microfibres when passed through the wash, rinse and spin cycles.

“It’s a really significant problem,” said Charlie Cox, Ocean Wise’s manager of microplastics solutions. “Synthetic textiles are the main source of microplastic pollution in the ocean.”

“They are being found everywhere that scientists have looked, including in the Arctic.”

Often defined as small plastic pollutants between five millimetres and one micrometre long, microplastics come from a variety of sources — from the breakdown of plastic garbage to microbeads in cosmetic products.

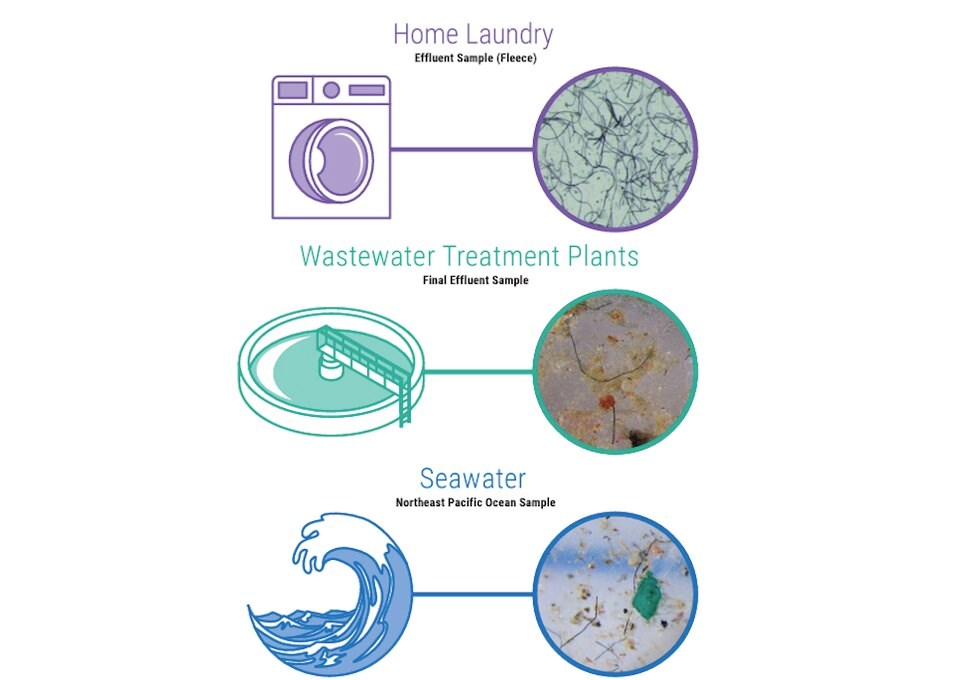

One of the largest sources of the tiny pollutant come from the clothing in our washing machines. Every year, microplastics shed from clothing in the wash sneak through wastewater treatment facilities and fill global oceans with 40,000 tonnes of pollutants so small they’re often invisible to the human eye. That’s equivalent to the weight of roughly 445 blue whales, past past studies have found.

Microplastics everywhere

Scientists have documented zooplankton that consume microplastics in the ocean have their growth disrupted. That's a major concern for an animal that forms a vital base for the marine food web.

From small spineless ocean creatures to fish and big marine mammals, microplastics are passed up the food chain by larger and larger predators.

In B.C.’s marine ecosystems, that accumulation is considered an “emerging threat” to a bilateral annual report from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Environment and Climate Change Canada.

It appears humans are also not immune to the pervasive impacts of plastics. Research has found microplastics are inhaled, absorbed through the skin and consumed through food and water — all eventually ending up in our lungs, livers, kidneys and even placentas.

In a first-of-its-kind study last year, researchers from the United Kingdom’s University of Hull found ingesting or inhaling high levels of microplastics in contaminated drinking water, seafood and salt may lead to cell death and allergic reactions. Further research into how the body excretes the plastics is required to understand the true level of risk, noted the authors.

And in an Italian study published earlier this year, researchers examining the breast milk of 36 women found microplastics in over 75 per cent of the samples. Patient data showed no links between the presence of microplastics and patients' age, use of personal care products, or food consumption habits.

Their conclusion: ubiquitous microplastic presence makes “human exposure inevitable.”

“The signs are concerning,” said Cox. “It’s not feasible to remove these fibres from the ocean once they get there. So we need to get as close to the source as we can.”

Going to the source

To carry out the Ocean Wise study, researchers at the Vancouver lab tested loads of synthetic laundry in 10 washing machines through 21 wash conditions. The wash cycles varied in water temperature and the rate of the spin. In each case, they captured and measured the weight of the plastic fibres shed from the clothing.

Past studies have suggested washing at a lower temperature reduced plastic shedding. But the Ocean Wise study didn’t find a statistically significant change, “probably because we did not test temperature as an independent variable,” notes the study.

In all the machines — including on soon-to-be-released Samsung washers with microfibre lint filters and newly programmed wash conditions — lower peak wash speeds and lower operating rates tended to have the biggest impact on reducing the number of microplastics shed into the environment.

Describing the results as “a game-changer for ocean health,” the report called on other washing machine manufacturers to produce products with built-in gentle, low-agitation wash cycles.

“What we're encouraging now is for other washing machine manufacturers to follow Samsung’s example and start designing low-shedding settings and to meet that standard,” said Cox.

Combined with clear labelling and messaging to consumers, such machines could reduce the shedding of microplastics by 35 per cent in North American homes, the report said.

Long-term, Cox says the hope is to create a regulatory standard that could accompany Canada’s recent move to ban six kinds of single-use plastics by 2023, including straws, checkout bags, cutlery, hard-to-recycle food containers, ring carriers and stir sticks.

Cox says it’s too early to suggest regulations on reducing microfibres. First, other manufacturers need to take on testing and innovation in their own products to understand which part of the washing cycle is shedding the most microplastics.

“Where's that actually happening?” Cox said. “And when we understand more about the specifics, then we can really take that to the regulators, take that to policymakers and make it really clear exactly what needs to happen.”

How you can reduce your microplastic footprint

Over the past six years, Ocean Wise’s plastics lab has been working with a number of companies to research how to reduce the spread of plastic microfibres.

In the past, that has meant researching and advising clothing manufacturers what kind of materials shed the most microfibres.

Last year, Ocean Wise released a number of consumer guidelines on how individuals can reduce the release of microplastics into the environment.

Consider washing your clothes less often. When you do throw in a load of laundry, turn on the cold water and gentle settings, and use a microfibre filter, suggests the Ocean Wise research. Or go even closer to the source.

As Cox put it: “Buy less fast fashion. All of these loads have an environmental footprint.”