The professor babbles on about fiscal financing.

Susan Chapelle can’t focus. She sits at a desk in the middle of the room, her deep, dark-brown eyes fixated on her laptop. The sentences streaming out from the Simon Fraser University instructor join the storm of words swirling in her mind; snippets of a radio interview the Squamish councillor heard that morning.

“Who were these women?” “Were they into S&M?” “Why had they not gone to police?” The commentators had asked a relentless barrage of questions, all focused on the victims rather than the alleged perpetrator.

It was everywhere. Pictures of the baby-faced CBC radio host Jian Ghomeshi filled news sites, as whispers of assaults seeped into the media. Ghomeshi retaliated with a line about a “jilted ex girlfriend.”

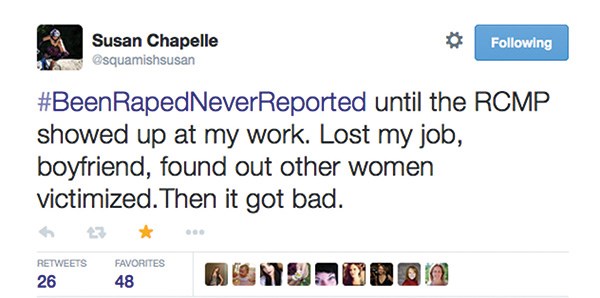

The frustration was paralyzing. And then, after class on the way back to her parked car, Chapelle sees it on her cellphone; a string of confessions streaming down Twitter. Her fingers texted rapidly. Her eyes land on the large blue “Tweet” button. Chapelle’s lungs fill with air; she holds her breath and clicks.

Chapelle was 26 in 1991 when she was drugged and raped by Canada’s worst serial rapist. She visited Selva Kumar (Richard) Subbiah’s house under the notion she was buying a potbelly pig. It was two o’clock in the afternoon. The 32-year-old offered her a glass of wine. Nine hours later Chapelle awoke confused. Her clothes were on backwards and she felt sore. Subbiah told Chapelle she’d passed out, before he drove her back to her little bungalow in the Beaches area of Toronto.

Sitting in a quiet room at Howe Sound Brew Pub for an interview with The Squamish Chief, Chapelle explains her thought process that awful night.

“I knew something really bad had happened,” she explains. “When I got home I felt really crappy about having gone to his house in the first place, that I had a glass of wine with him.”

A week later the potbelly pig and a flower arrived on Chapelle’s doorstep. But even that wasn’t enough to prompt Chapelle to go to the police. She chalked it all up as a bad experience and a result of her own stupidity.

Chapelle wasn’t alone. Of the approximately 1,000 women Toronto police estimate Subbiah sexually assaulted since his arrival in Canada from Malaysia in 1980, none reported him. What eventually led to Subbiah’s conviction on 70 offences involving more than 30 women was his little black book. Subbiah documented his victims’ names, photographed them and rated them on a scale of 1 to 10.

The tale of silence is one that unfortunately is common, said Shana Murray, Howe Sound Women’s Centre’s manager of community programming. As many as three-quarters of women who are sexually assaulted keep the crime a secret from police, she says.

With such hush-hush surrounding the incidents, it’s difficult to get an accurate count of the number of women in the Sea to Sky Corridor who have been sexually assaulted, Murray says. According to a Ministry of Public Safety-Solicitor General’s publication of BC Crime Trends from 2000-2009 – the most recent statistics – there were 53.4 reported sexual offences in the Sea to Sky Corridor per year. Given adjustments for population size, that represents 172 offences per 100,000 people – a rate almost three times higher than urban centres such as Richmond and the North Shore.

While a large chunk of the crimes can been pinned on Whistler, Squamish is in no ways squeaky clean, Murray says.

“Since the summer, a handful of women have come forward,” she says.

Yet that situation is at odds with what the Squamish RCMP detachment describes. The department’s spokesperson Sgt. Wayne Pride calls the cases very “uncommon.” It’s a disconnect both organizations hope to fix by improving the process of reporting while also battling the offence.

Taking the issue seriously needs to be on the forefront of community and government organizations’ minds and men need to help lead the charge, Murray says.

The women’s centre aims to inform the population while young. The group offers a program for Grade 10 students throughout the corridor. The youth education initiative teaches teenagers about health relationships and understanding consent – exploring issues such as the fact drunken individuals are not able to provide consent.

While it’s only a two-hour course, it’s a start, Murray says. But the women’s centre isn’t sure it will be able to scrape together the $8,000 needed to keep the course running.

Most women’s centres and sexual assault support

services face a lack of reliable funding, says Irene Tsepnopoulos-Elhaimer, Women Against Violence Against Women (WAVAW) spokesperson. Every year there are approximately 472,000 self-reported cases of sexual assault across the country according to Statistics Canada, yet only four of 16 Status of Women Canada offices remain open. This is the federal government organization tasked with increasing women’s economic security, encouraging leadership and ending violence against women and girls, Tsepnopoulos-Elhaimer says.

Ottawa also closed the doors on the Ministry of Women’s Equality 12 years ago.

“That was devastating,” she says.

The lack of funding also affects the resources women can turn to in a time of need, Tsepnopoulos-Elhaimer says. In Squamish, women who are raped and want to press charges have to travel to Vancouver so that experts can gather samples needed in a trial. The forensic examination must be conducted within 72 hours of the sex crime, which can present challenges to women without transportation.

But truly addressing sexual assault requires a lot more than money, Tsepnopoulos-Elhaimer says. It requires a deeper look into Canada’s social fabric, from video games depicting Elven creatures with gravity-defying breasts that can be fondled if a player completes a task, to Hollywood glamorizing men forgetting the names of one-night stands. It comes down to how we respect one another, Tsepnopoulos-Elhaimer says.

“This is really questioning deep, deep held attitudes about being human.”

•••

After police found her name in the black book, Chapelle’s testimony in 1992 helped put Sabbiah behind bars for 25 years. It was a difficult process, she admits. Her boyfriend split up with her through the trying time and she lost her job as a stage technician when police came to her work to accompany her to the police station. The images of the 91 pictures police showed her of naked women passed out and draped on beds and couches will stick with her forever. There was little support and victims were told to talk to their priests. But Chapelle still wonders what the outcome would have been if she had reported the crime; she wonders how many women could have been spared.

Police recognize that reporting a sexual assault is a brave and daunting step, but one that can help change and protect other people, Sgt. Pride says. RCMP are continuously working on better procedures surround sexual assault, he adds.

“We want that message out there.”

Chapelle hopes sharing her story will encourage and empower men and women to advocate for equality. Putting her story out to the world came with a sense of relief. Prior to her tweet on Oct. 30, Chapelle hadn’t told anyone about the attack since her mother commented on how “silly” she was for going over to a stranger’s house.

The day after she issued her tweet, Chapelle anticipated (and partly dreaded) being showered with sympathy. What she experienced instead took her by surprise.

“The people around me were like ‘That happened to me too,’” she said, as she shook her head in disgust. “How sad is that?”

•••

Sex assault victims face drive to city for forensic exam

Squamish sexual assault victims face a long drive to Vancouver after being raped to document evidence against the perpetrator.

Currently anyone in Squamish considering taking a sexual assault case to trial has to travel to Vancouver General Hospital for a forensic examination following the assault.

This presents big hurdle for victims planning to report the crime, said Shana Murray, the community program manager for the Howe Sound Women’s Centre. The individuals have to receive the examination within 72 hours of the sex crime. For people who don’t own vehicles, transportation options to Vancouver are limited, Murray said.

The forensic services for all of the Lower Mainland have been consolidated at Vancouver General Hospital, said Laurie Leith, Vancouver Coastal Health’s operations director. Some rural communities have created different models to serve their residents, she noted.

The health authority has been discussing providing the forensic services in Squamish, but it’s not as simple as designating a room at Squamish General Hospital. The infrastructure cost of setting up the service would likely be approximately $30,000, according to Leith. The health authority also needs to find physicians interested and able to take on the extra training, she said.

“The dollars are really not the biggest obstacle,” she said, adding that different models come with different price tags.

The health authority has identified three possible physicians that are interested in assisting with providing the program. The authority met with Squamish hospital staff last Tuesday, Nov. 25, and the topic was on the agenda.

“We are currently in discussions with our Sea to Sky physicians to see if there is a model that we can come up with that would be assistance and make sense,” Leith said.

manager of community programming, says the majority

of women do not report their assault to police.

The women’s centre is launching a campaign to task

citizens with getting involved in stopping questionable situations.

Make your move

Don’t be a quiet bystander when you suspect a sexual assault might occur. That’s the message of the Howe Sound Women Centre (HSWC) new campaign against sexual assault.

Earlier this year, the centre aimed to launch its “Don’t Be That Guy” campaign, but owners of some Sea to Sky corridor bars said the initiative was too hard-hitting. The campaign featured posters such as a photo of a man helping a drunken woman into a car with a caption, “Just because you help her home, doesn’t mean you get to help yourself.” While it had been successfully rolled out in Edmonton and Vancouver, Sea to Sky bars weren’t biting.

After going back to the drawing board, the centre came back with the latest plan “Make Your Move.” The new campaign is more encompassing, involving the entire community, said Shana Murray, community program manager for the HSWC. Posters beckon bystanders to ask questions and step in when necessary.

“We feel this one helps raise awareness, breaks the silence around sexual assault and encourages bystanders to take a stand,” she said.

The centre will also offer bar managers and staff training to spot potential problems. The course will be offered for a small fee and teach employees to watch for red flags among the patrons and steps to interject and navigate a situation.

“One small step of intervention can make a dramatic difference for that person,” Murray said.

– with files from Alyssa Noel

•••

Police explain steps for reporting a sex crime

Assault investigations are high priority with the police, Squamish RCMP spokesperson Sgt. Wayne Pride says.

“Re-victimizing” anyone is the last thing that police want, he noted. But with any police investigation, officers must obtain the facts, regardless of how difficult the facts may be to discuss. To have a victim re-live an event is difficult, but it’s necessary to obtain sufficient evidence to pursue charges, Pride said. Police require an account of the crime.

The investigation is done with compassion and consideration, Pride said. Privacy and trauma to the victim are important considerations. When an incident is reported, an interview will be conducted and a statement obtained if the victim is cooperative.

Depending upon the facts of the incident, some victims are hesitant, and it is the police’s job to work with the victim and her or his family and friends, if applicable to the situation, Pride said.

Some sexual assault investigations can be complex and sensitive. The investigator’s task is to be supportive to the victim and work with that person to ensure that not only are they comfortable sharing their experience, but also that they realize they are doing the right thing for the right reasons, Pride said.

“Although there are many experiences out there from victims, feedback received with frequency has been that in taking the necessary steps to assist in an investigation and bring a suspect to justice has helped many in dealing with the trauma,” Pride said.

Upon the initial interview and statement-taking, the next steps are evaluated. If sufficient evidence exists regarding the identification of the suspect, the suspect will be arrested. As in any investigation, upon arrest an individual must be advised of the reason for the arrest, Pride said.

The suspect will be booked into police cells, given the opportunity to contact a lawyer or legal aid and given the opportunity to provide a statement.

Upon an initial arrest, a subsequent trial date is set so that at a later date all of the additional investigation facts can be presented formally in a court of law. An investigator complies a report that is submitted with crown counsel, who reviews the facts and may request clarifications or additional information in preparation for court. The officers liaise closely with crown counsel in such investigations.

The police have a victim’s assistance resource person who, if agreeable to the victim, can liaise with her or him throughout the investigation and can attend court if asked on some cases.

The investigation and court proceedings can and will be explained to victims to ensure they are fully aware of what is to occur and mitigate any feelings of doubt, wonder or concern.

Female officers are frequently involved or requested by female victims, and RCMP assign a female officer to the case when feasible, Pride said.