As the saying goes, when we know better, we can do better.

Synthetic fibres are invading the Arctic Ocean and a local is one of the key people behind a recent study that revealed this troubling fact.

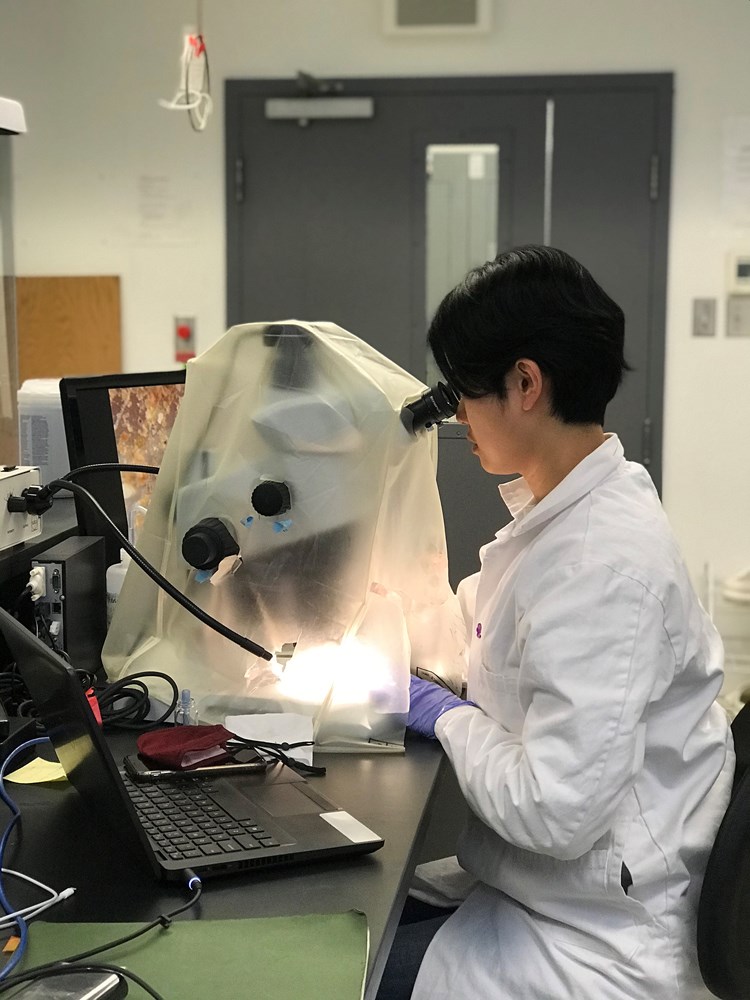

Squamish's Anna Posacka is the co-author of the study Pervasive distribution of polyester fibres in the Arctic Ocean is driven by Atlantic inputs, and research manager at the Ocean Wise Plastics Lab, which has produced the comprehensive analysis of microplastics in the Arctic Ocean.

"Synthetic fibres make up approximately 92% of microplastic pollution found in near-surface seawater samples from across the Arctic Ocean. And about 73% of those fibres are polyester and resemble fibres used in clothing and textiles," reads a news release on the study, which was published in the international scientific journal Nature Communications.

The project also had support from Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO).

The research involved analyzing water samples from 71 locations from the European and North American Arctic, taken from aboard One Ocean Expeditions RV Akademik Ioffe and by Fisheries and Oceans Canada Arctic programs aboard the Canadian icebreakers CCGS Louis S. St-Laurent and CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier in 2016.

"The analysis took quite some time," said Posacka, who moved to Squamish from Vancouver three years ago. "Microplastics are very difficult to study because of their size but also because they have many sources."

The research highlights the role that textiles, laundry, and wastewater discharge have in the contamination of the world's oceans.

“The Arctic Ocean, while distant to many of us, has long provided` food and a way of life for Inuit communities,” said Dr. Peter Ross, lead author of the study, special advisor to Ocean Wise and adjunct professor at Earth, Atmospheric and Ocean Sciences at UBC in the news release. “The study again underscores the vulnerability of the Arctic to environmental change and to pollutants transported from the south. It also provides important baseline data that will guide policymakers in mitigation of microplastic pollution in the world’s oceans, with synthetic fibrews emerging as a priority.”

The study found the average concentration of microplastics to be around 40 microplastic particles per cubic metre and the data leads them to believe an important source of microfibres in the Arctic is likely the countries surrounding the Atlantic Ocean.

There is still much researchers don't understand about the impact of these microfibres, but something that has been reported has been blockages of marine animals' intestines, which potentially reduces the caloric intake of those species.

Basically, if they ingest large quantities of these fibres, they feel full from eating the wrong things.

And it is known from laboratory experiments that zooplankton that are ingesting or interacting with microfibres, may get their feeding appendages entangled, which impacts their ability to feed. It can also impact their reproduction.

There needs to be more of an understanding of what other species are vulnerable to negative impacts, which is something Posacka said her lab is investigating.

"There are huge research gaps," she said.

Most microfibres are captured by wastewater treatment facilities, where such facilities exist, but that isn't enough, in the big picture, Posacka told The Chief.

"While that retention is quite high — so up to 99% — on an annual scale and long-term scales, the emissions of microplastics with the treated effluent can be quite significant," she said, adding her team estimates that in Canada and the U.S., that amounts to more than 800 tonnes of microfibres in the ocean every year — equal to 10 blue whales in weight.

An important question is what happens to the fibres that are captured by the facilities, Posacka said.

"Because they end up in sludge, so all those solids that are in wastewater and oftentimes, sludge would be treated and applied as biosolids... and that can be applied to agricultural land for fertilization purposes and so there's a potential for these microfibres to return to contaminate the terrestrial environment," she said.

She said there is some evidence that microfibres from people's dryers are travelling by air and getting into the ocean.

"The takeaway is really that in general one of the important opportunities for addressing this problem, is to improve the quality of our materials — and that is an important one that industry needs to play to help with that — but as consumers, we should be watching out for our fashion habits, the more we consume the more of that polymer is in our society," she said, adding reusing and remaking of textiles will help.

There are also lint traps you can install into the washing machine that can capture some of the microfibres that are normally released.

"Reducing fibre releases from textiles represents a significant opportunity to curb marine microfibre pollution. And together with Ocean Wise's Microfiber Partnership, some forward-looking companies and initiatives are looking for ways to address this problem," the news release states.

Unfortunately, there isn't much at this point we can do retroactively, to clean up the fibres that are already in the ocean, Posacka said.

"It would be very, very challenging because we are dealing with such small particles that are now part of the ecosystem. And, within water where we have those microfibres, we also have phytoplankton and we have zooplankton and other creatures. So when we start to think about removal, we need to ask ourselves, what are the potential knock-on effects?"

Where there are high levels of microfibres, such as in sediment, citizens can ensure communities don't dredge that environment and cause more damage, she said. "That would lead to more of the microfibres being re-suspended in the water column. Those are the types of things we can think about."

Posacka said a point of reflection for her was that this isn't the first case where a pollutant from the south is entering the Polar region.

"I think it really resonated with me, particularity for plastics, is that it is a trans-boundary issue. Things that we do in one region can affect an ecosystem that is very far away and often time there are people in this eco-system who rely on it," she said.

"It is a moment of reflection, but also energy — to work to identify solutions together with my team. There are solutions. We just need to do some research around some of them, so that we can better understand the best approach."

Some solutions are offered here and here.