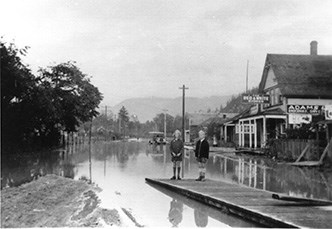

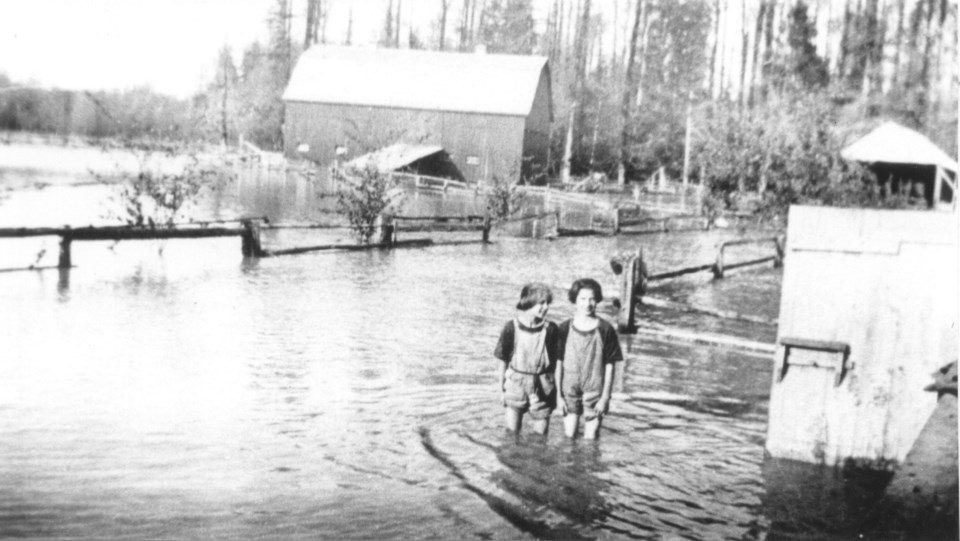

Ellen Grant remembers riding in a canoe when she was five years old in the 1940s, bringing supplies to Brackendale. Her grandparents were cut off from the town when the river overflowed.

She remembers seeing salmon swimming down Judd Street, and people chasing them back into the creek.

In high school, she heard the foreboding sound of the rushing river.

“I can remember listening to the rivers roaring and watching the flood waters coming closer and closer… it’s sort of spooky to hear the water roaring,” she said. “A river becomes something else when it’s in flood.”

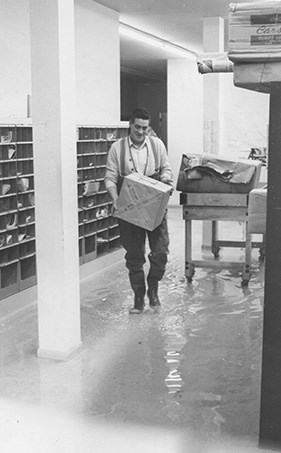

In Squamish, nothing is as certain as death, taxes and flooding.

Squamish is at risk of flood from all sides: from overflowing rivers to runoff from the spring snow melt, which, compounded with heavy rainfall, can make some level of flooding a regular occurrence. Climate change adds to this problem: as glaciers and ice sheets melt, ocean levels rise, and Squamish is only five metres above sea level.

Most of Squamish is located on a floodplain, an area of land adjacent to a stream that is regularly or periodically inundated during a flood. One exception is a portion of the Garibaldi Highlands northeast of Mamquam Road and Highlands Way South.

The western portion of Garibaldi Estates and Brackendale are the area at highest risk in Squamish, as well as the floodplain north of Mamquam River.

And in Brackendale, the situation is even more dire than an occasional incident of high water: it’s on the Cheekye Fan, a land formation created by sediment deposited from water flow and landslides, which is at risk of landslides, stream floods, sediment deposits, land erosion, and shifts in watercourse.

Living with all that risk is something many in Squamish likely try not to think about, and getting flood insurance is something they may think of even less.

Aaron Sutherland, vice president for the Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC) for the Pacific region, says flood insurance is relatively new in Canada, but there is a growing market for it.

“As we’ve seen our climate change, as our weather gets warmer, as it gets wetter, as we’re seeing more extreme rainfall events, we are seeing more flooding,” he said. “As our industry has seen more incidents of flood, we’ve responded by creating flood insurance products for your home.”

But there is an irony to flood insurance: the more you need it, the less likely you’ll be approved for it.

“Let’s be frank: flood insurance, like any insurance, is priced based on risk. And while the overwhelming majority of flood insurance is eminently affordable, those living at the highest risk may see very high premiums that reflect that, or they may have a difficulty purchasing flood insurance at all,” said Sutherland.

“If they’re living right in the floodplain, or an area that has a history of significant flood events, insurance price increases as your risk increases.”

When someone applies for flood insurance, brokers search their property by postal code. A Squamish insurance broker made a preliminary search for properties at this reporter’s request and found flood insurance was not immediately available for several properties in Brackendale (there is a workaround for finding postal codes of properties that use P.O. boxes). Some brokers may insure properties in Brackendale, but many will not.

Base rates for flood insurance vary widely and are impossible to generalize because they are determined by your existing home insurance policy and home insurance building limit.

For those few Brackendale property owners that may find a company willing to insure them, they will be stuck with very, very high premiums, and the plan will be unlikely to cover damage from saltwater flooding. That insurance is a separate product from regular overland flood insurance or insurance for sewer backups and is even more expensive. In Squamish, where there is a real risk of saltwater flooding, getting this type of insurance is especially difficult.

Squamish Nation band members are in luck here: the Nation has a blanket policy that insures all properties and land the Nation owns, which is likely to include flood insurance, according to the Squamish Nation’s manager of accounting, revenue and taxation Cathleen Smith.

The Nation covers the majority of insurance, and the government likely will cover the rest, she said.

“Whatever we can get, we purchase,” she said. “The Nation insures the contents and structures for the band members.”

Everyone else in Squamish may have to rely on the government for help should their home be flooded.

But that help won’t be coming from the District of Squamish.

Corinne Lonsdale was a councillor for 25 years until 2011. Up until her departure, getting a building permit required signing a covenant that let the District off the hook for covering any damage that may be caused by a landslide for the majority of properties in Brackendale.

“If you wanted to do any additions to your homes and lived in the actual area that would be impacted by that debris flow and in that floodplain area, you had to sign a covenant that would hold the District of Squamish harmless if there was water damage to whatever it was you were adding on to your place,” she said. “If you needed a building permit, you needed to have a covenant that you are taking responsibility for whatever you’re putting there.”

The District’s new Integrated Flood Hazard Management Plan, however, seeks to reduce the risk of serious floods, particularly in Brackendale, Garibaldi Estates and the Squamish Nation reserve lands.

The plan calls for upgrades to and raising of existing dikes, a new sea dike to prepare for sea-level rise, raising new development above the flood construction level, limiting development in the highest hazard areas, and increasing development in low- or no-risk areas.

Mayor Patricia Heintzman said the District has identified high-risk areas and is prioritizing them.

But when it comes to what happens after a disastrous flood, that’s out of their hands.

“That’s up to the individual and the province to figure out that scenario; that’s not up to the municipality,” she said.

The B.C. government provides disaster financial assistance in case of uninsurable events like overland flooding and some landslides to some homeowners, residential tenants, small business and farm owners, and charities. The word ‘uninsurable’ is key here: residents have to be unable to purchase private insurance, or they will likely not be covered.

For approved claims, the provincial government provides 80 per cent of the amount of the total eligible damage that exceeds $1,000 up to a maximum claim of $300,000. But you can’t claim seasonal or recreational properties, hot tubs, patios, pools, luxury and recreational items.

Now that private insurers are offering flood insurance, which could be a problem for people who have the option of buying insurance, even if it is “prohibitively expensive,” says Heintzman.

“People don’t even know they can get it because for so long you couldn’t get it, and that potentially leaves the homeowner at risk because the government will say ‘well you should have gotten flood insurance,’” she said. “You want people to do their due diligence, but what we can do as a municipality is work pro-actively toward ensuring that we have a well-planned, robust flood protection system.

“You’re in a floodplain; you’re always going to be vulnerable, so you’re never going to get rid of 100 per cent of the risk.”

While Squamish residents may not be facing flooding today, there is no guarantee it won’t happen tomorrow.

Just ask Ellen Grant: she’s seen too many floods to count, and knows what living near bodies of water, like the Mamquam and Squamish rivers, is all about.

“It’s a very, very powerful thing, and so often we take it for granted that we can live with it,” she said. “But you always remember that nature is a tremendous force you can never really tame.”