Please note that this is an archival story originally published on Jan. 18, 2019.

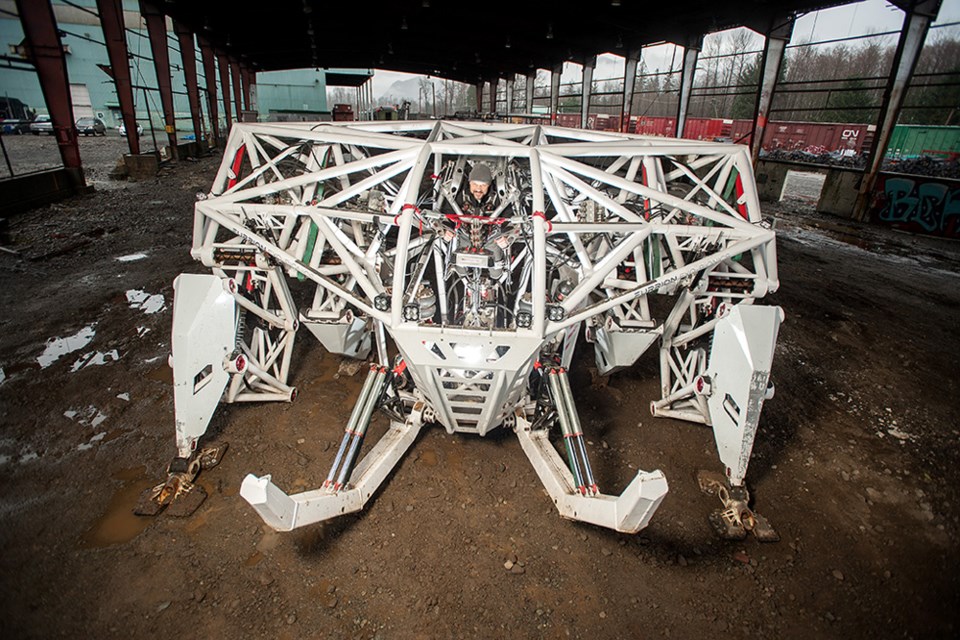

It is just a giant robot splashing through puddles in an empty, open-air warehouse, with the Stawamus Chief as its backdrop.

Nothing unusual in that.

Wrong.

Prosthesis is the world's first purpose-built, off-road racing mech, its inventor, pilot and lead engineer, Jonathan Tippett, told The Chief.

The ultimate goal is to race it in a league of teams that compete against each other.

Without much fanfare, Prosthesis has been put through its paces in Squamish's rail yards for the last couple of months.

The 3,900 kilogram, 4.2-metre-high, five-metre-wide machine, which its creators call the anti-robot, runs on a custom-made lithium-ion battery and electro-hydraulics.

Squamish was chosen as a location for testing Prosthesis because it had the space needed and is close to the team's home base of Vancouver, according to the project’s mechanical engineer Sam Carter.

"It is the heart of outdoor adventure sports, so we thought it was a pretty good fit," he said.

Prosthesis has been in the works for more than a decade but came together in its current form in 2016.

Over the years, there have been fits and starts in getting the machine to do what the team wanted it to do — walk.

Tippett describes being beyond excited when his dreams finally evolved into the actual built machine two years ago.

His enthusiasm waned slightly when he powered it up and Prosthesis proceeded to faceplant, repeatedly.

"I wasn't crestfallen. It wasn't a super disappointment," he said. "I was like, 'I will get it on the next one — tomorrow.'"

The work continued.

Prosthesis — with its custom steel pipes, custom joints, market farm equipment and hydraulic parts — has taken untold volunteer hours and money to get to the point it is today.

The next generations will be faster and lighter.

"The first machine is proof of concept. We have to demonstrate that the technology works. Get it to the point that it looks exciting and someone would want to invest in it, so we can build the next iteration and next generation," said Carter.

Future robots would likely cost about $2 million each if built in bulk.

While it can currently walk at about 6.5 kilometres per hour, the next step is to have it run.

Tippett got the idea for the machine when he saw a sculpture of dinosaur legs at a Burning Man festival in 2003.

Initially, it was an art project with the aim to build a walking machine that a human would control. The racing league concept gave context to the art piece.

The project was moved forward over time by the eatART Foundation, a charity launched by Tippett to foster art research with a focus on large-scale, technically sophisticated pieces.

The team is currently in partnership with Furrion, an international technology company. This partnership led to the formation of Furrion Exo-Bionics, which will continue to develop the technology and build the new sport of mech racing, according to Tippett.

With the third generation of the control system currently installed in Prosthesis, the team is off to California for more practice with the machine.

"This stage we are at now is breaking through the ice," Tippett said, with a big smile. "I have been fantasizing about what we are going to do in the next six months, for the last 12 years."

While they are soon heading to warmer climes, Prosthesis and its creators may be back in Squamish next summer, Carter said.