ALBANY, N.Y. — New York is poised to join a growing number of states that have legalized marijuana after state lawmakers reached a deal to allow sales of the drug for recreational use.

The agreement reached Saturday would expand the state's existing medical marijuana program and set up a a licensing and taxation system for recreational sales. Lawmakers are expected to vote on the bill Tuesday, the earliest they could consider it. Legislative leaders hope to vote on the budget Wednesday to meet the deadline of having a budget in place by April 1.

It has taken years for the state's lawmakers to come to a consensus on how to legalize recreational marijuana in New York. Democrats, who now wield a veto-proof majority in the state Legislature, have made passing it a priority this year, and Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s administration has estimated legalization could eventually bring the state about $350 million annually.

“My goal in carrying this legislation has always been to end the racially disparate enforcement of marijuana prohibition that has taken such a toll on communities of

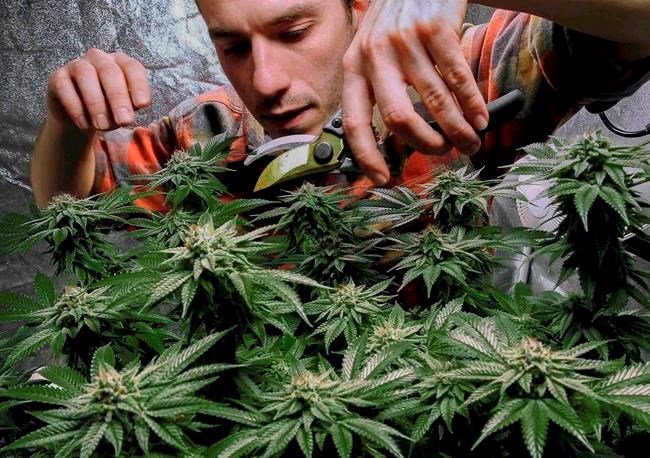

The legislation would allow recreational marijuana sales to adults over the age of 21, and set up a licensing process for the delivery of cannabis products to customers. Individual New Yorkers could grow up to three mature and three immature plants for personal consumption, and local governments could opt out of retail sales.

The legislation would take effect immediately if passed, though sales wouldn’t start until New York sets up rules and a proposed cannabis board. Assembly Majority Leader Crystal Peoples-Stokes estimated Friday it could take 18 months to two years for sales to start.

Adam Goers, a

“There’s a big pie in which a lot of different folks are going to be able to be a part of it,” Goers said.

New York would set a 9% sales tax on cannabis, plus an additional 4% tax split between the county and local government. It would also impose an additional tax based on the level of THC, the active ingredient in marijuana, ranging from 0.5 cents per milligram for flower to 3 cents per milligram for edibles.

New York would eliminate penalties for possession of less than three ounces of cannabis, and automatically expunge records of people with past convictions for marijuana-related

And New York would provide loans, grants and incubator programs to encourage participation in the cannabis industry by people from minority communities, as well as small farmers, women and disabled veterans.

Proponents have said the move could create thousands of jobs and begin to address the racial injustice of a decades-long drug war that disproportionately targeted minority and poor communities.

“Police, prosecutors, child services and ICE have used criminalization as a weapon against them, and the impact this bill will have on the lives of our oversurveiled clients cannot be overstated,” Alice Fontier, managing director of Neighborhood Defender Service of Harlem, said in a statement Saturday.

Some other states that have legalized recreational marijuana have struggled to address the inequities that the drug wars have wrought.

Three years after Massachusetts voters passed a ballot initiative making recreational cannabis legal in the state, Black entrepreneurs complained in 2019 that all but two of Massachusetts’ 184 marijuana business licenses had been issued to white operators.

California voters legalized recreational marijuana sales in 2016 as well and invited people to petition to have old marijuana convictions expunged or reduced. But relatively few people took advantage of the provision initially.

Criminal justice reform advocates said New York's bill avoids that problem by setting up a process for marijuana convictions to be automatically expunged.

“We are very happy that the bill includes automatic expungement. It’s integral to addressing past harms,” said Emma Goodman, an attorney at the Legal Aid Society.

Melissa Moore, the Drug Policy Alliance’s director for New York state, said the bill "really puts a nail in the coffin of the drug war that’s been so devastating to communities across New York, and puts in place comprehensive policies that are really grounded in community reinvestment.”

At least 14 other states already allow residents to buy marijuana for recreational and not just medical use. Cuomo has pointed to growing acceptance of legalization in the Northeast, including in Massachusetts, Maine and most recently, New Jersey.

New York does not have a statewide referendum process as California and Massachusetts do, so only the Legislature has the power to legalize recreational marijuana, as it did with same-sex marriage in 2011.

Past efforts to legalize recreational use have been hurt by a lack of support from suburban Democrats, disagreements over how to distribute marijuana sales tax revenue and questions over how to address drivers suspected of driving high.

It also has run into opposition from law enforcement, school and community advocates, who warn legalization would further strain a health care system already overwhelmed by the coronavirus pandemic and send mixed messages to young people.

“We are in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and with the serious crisis of youth vaping and the continuing opioid epidemic, this harmful legislation is counterintuitive,” said an open letter signed by the Medical Society of the State of NY, New York State Parent Teacher Association, New York Sheriff’s Association and several other organizations March 11.

New York officials plan to launch an education and prevention campaign aimed at reducing the risk of cannabis among school-aged children, and schools could get grants for anti-vaping and drug prevention and awareness programs.

And the state will also launch a study due by Dec. 31, 2022, that examines the extent that cannabis impairs driving, and whether it depends on factors like time and metabolism.

The bill also sets aside revenues to cover the costs of everything from regulating marijuana, to substance abuse prevention.

State police could also get funding to hire and train more so-called “drug recognition experts.”

But there’s no evidence that drug recognition experts can tell whether someone is high or not, according to R. Lorraine Collins, a psychologist and professor of community health and health

“I think it’s very important that we approach that challenge using science and research and not wishes or unsubstantiated claims,” Collins said.

Collins pointed to a 2020 report from the American Civil Liberties Union that found that Blacks are almost four times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession compared to Whites, based on FBI statistics.

“Every New Yorker should be concerned about how these laws will be implemented or how those ways of examining drivers will be implemented in different communities,” Collins said. “It’s not likely to be equal.”

The bill allows cities, towns and villages to opt out of allowing adult-use cannabis retail dispensaries or on-site consumption licenses by passing a local law by Dec. 31, 2021 or nine months after the effective date of the legislation. They cannot opt out of legalization.

______

Peltz and Matthews reported from New York City.

Marina Villeneuve, Jennifer Peltz And Karen Matthews, The Associated Press