The air at the railway portal at Mile 10.58 near Horseshoe Bay smells of tar, oil and damp grass. Tangled blackberry vines and horsetails grow towards tracks neatly embedded in flat crushed rock. There are no trains coming, just a steady dripping sound that gets louder when water percolates down the jagged rock at the tunnel's entrance. Inside the tunnel, warning signs guard grim graffiti faces stencilled onto the smooth grey and black concrete arches that dissolve into the darkness towards a tiny pin prick of light more than two kilometres away.

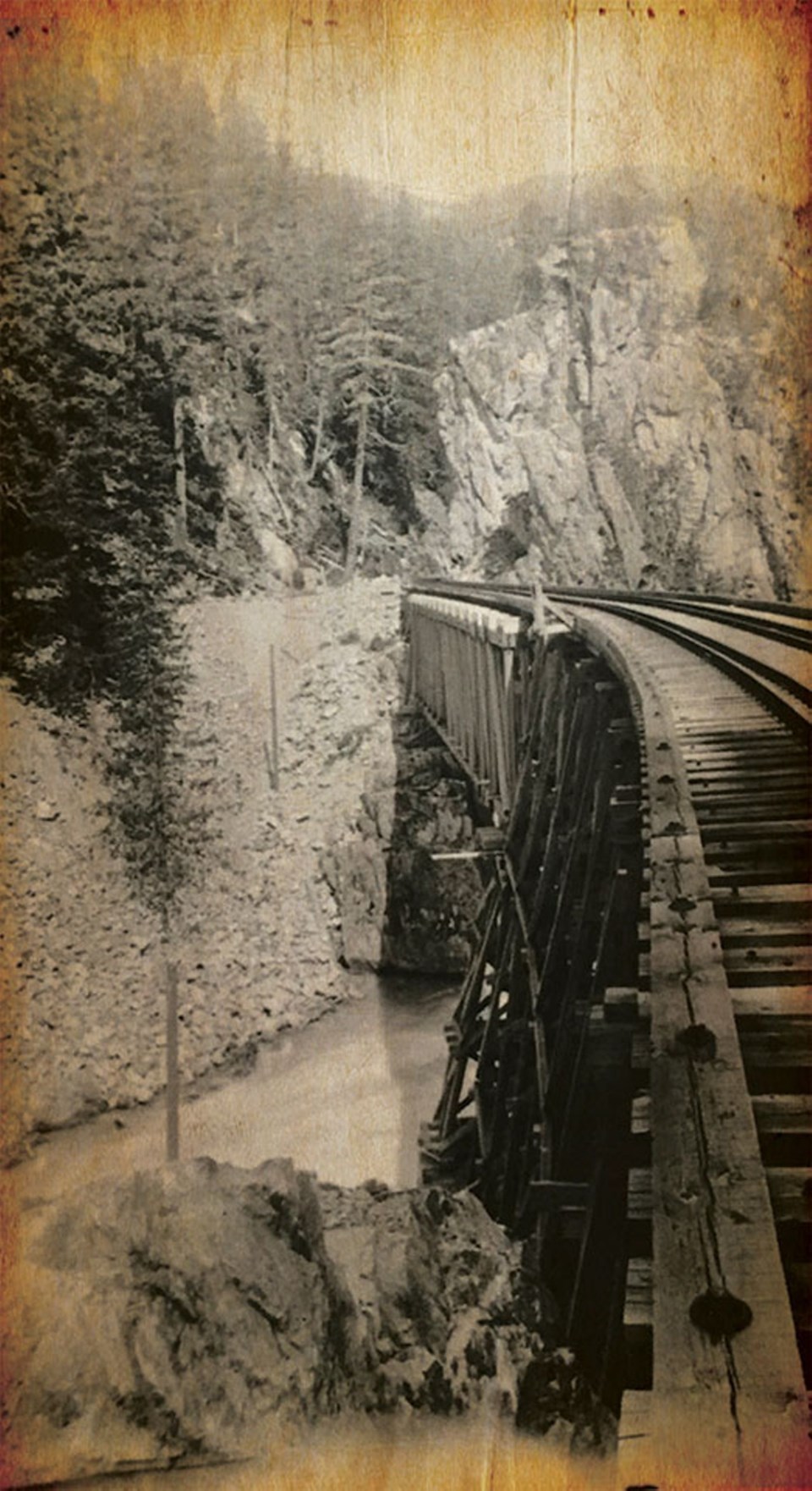

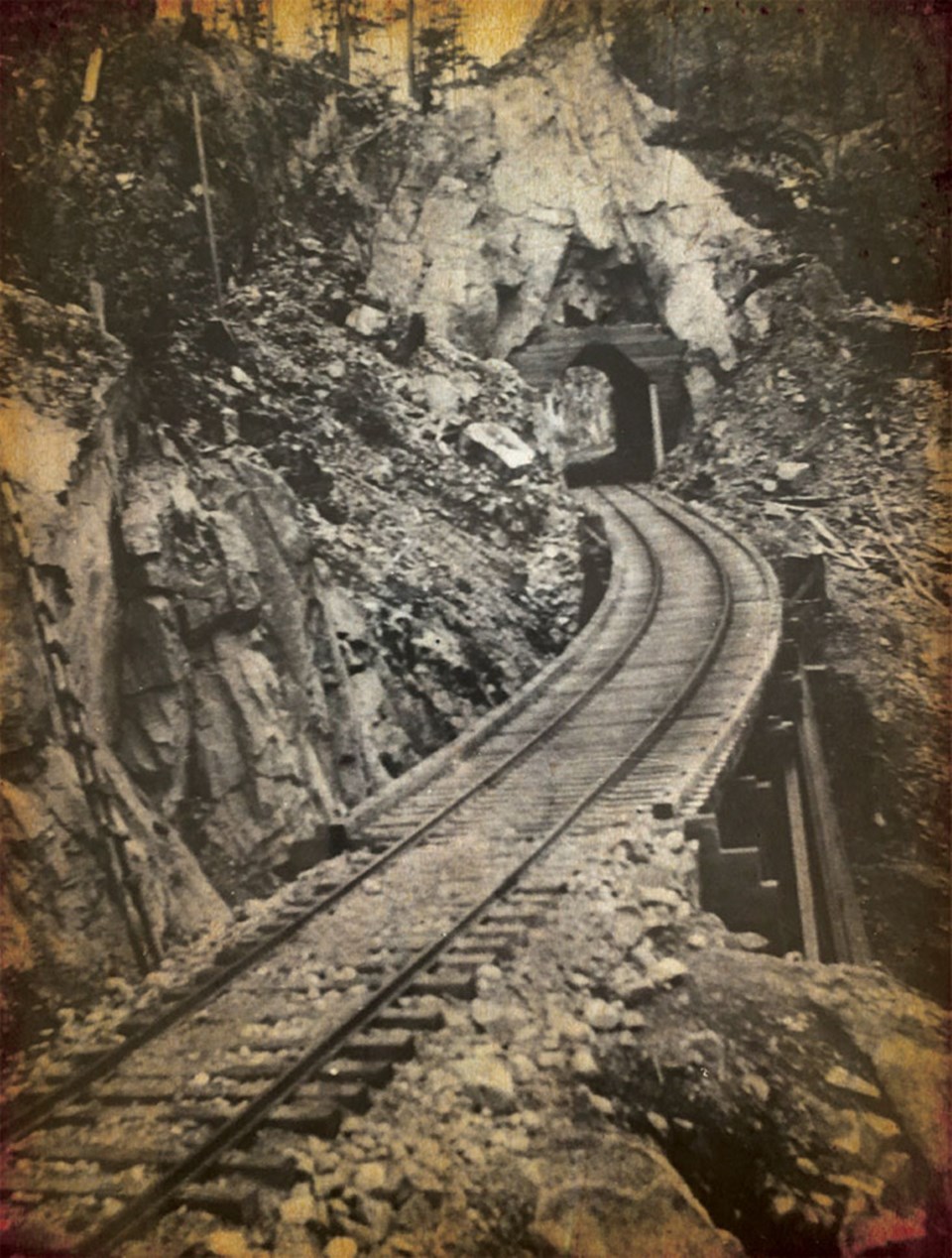

This section of the railway may have been considered straightforward enough by the builders, but when Canadian Pacific Railway surveyors travelled through the Cheakamus Canyon in the 1870's and 1880's looking for a line to the coast, they said building a railway was impossible. Even so, by 1910, a local consortium was determined the railway would be built. Several hundred men worked on the line from Squamish to Whistler, many residing at a camp on the Cheakamus River about 16 km out from Squamish. Other workers stayed at the Newport or King George Hotel in town and commuted to work. The crews worked 16-hour days, earning 75 cents to a dollar a day. In spite of almost insurmountable obstacles, the rail line was completed from Squamish to Whistler in 1915.

The job was fraught with hazards.

"Once you started blasting rock to create a tunnel, there was always rock above or below that was loose and could be knocked out by frost or just the vibration of the train running along," Trevor Mills, an archivist with the West Coast Railway Association in Squamish begins. "There were washouts and heavy rain and snowmelt could bring trees down."

The toughest part was where the track started climbing about 21 km north from Squamish at the Cheakamus siding.

"The hill starts right there and goes up into the mountains," Mills continues. "If you're not building a bridge, you're blasting through a tunnel or carving a shelf just wide enough to put the railway on. You'd drill in 12 feet (3.6 metres), set your charges, blow the charge in the tunnel and then haul the rock out. Then they'd drill in another 12 feet."

PLOWING ON

It a cost of roughly $3 million, constructing the railroad to Whistler took the better part of 1913 pushing north through the Cheakamus Canyon. When crews got up towards Whistler, they found their problems weren't over.

"There could be 15 feet (4.5 m) of snow at Whistler, which was hard to plow through with the equipment they had in those days," Mills explains.

When the railway was completed, it wasn't easy for homesteaders along the line either. One couple living in an old railway house got their water for washing from a steamer that stopped on Saturdays and filled seven barrels with boiling water.

Engineers had their own obstacles, the least of which was dealing with the piece of canvas that hung down the back of the cab in the engine; in winter, snow came right through the window.

In 1915, people were arriving in Squamish in droves, coming up Howe Sound from Vancouver on Union Steamships heading to Rainbow Lodge and other rustic lodges springing up along the corridor. The rail line had opened the country.

"It would take farmers from Pemberton three or four days to get to Vancouver over the cattle trails with their livestock," Mills says. "The farmers were very enthused about putting the railway through so they could cut that time down to a day."

The railway also created a huge real-estate boom in Pemberton. People wanted to settle in the valley because it was beautiful farmland. Pemberton would become a rich farming region known for its thriving potato, pumpkin and tobacco crops. In 1911, land prices doubled in the Pemberton Valley, from $500 to $1,000 an acre. The belief was that the soil was so rich that a single crop would pay for the land.

CULTURE CLASH

The railroad has been fundamental to people living in Squamish, Whistler and Pemberton, but there has always been turmoil surrounding transportation issues in the Sea to Sky corridor. In 1953, there was animosity between those wanting to build a highway along Howe Sound and those wanting a rail line from Squamish to North Vancouver. In March of that year, the Legislative Railway Committee said constructing the Pacific Great Eastern Railway and a highway along Howe Sound would be virtually impossible. When construction began on the two-lane Squamish Seaview Highway from Horseshoe Bay to Squamish in February 1955, workers claimed it was the most difficult road ever built in British Columbia.

"Sometimes it's tough even finding a place to set the road," reported highway engineer George McCabe, who oversaw much of the project, at the time.

There was also a lot of pride in railway heritage at the time, and some Squamish residents weren't so welcoming of the highway.

"Putting in the highway meant a huge change for Squamish in that a whole bunch of people from Vancouver would be coming into town," Mills recounts. "Squamish was a closed town because you couldn't get access to the city except by steamship. The whole culture of the town changed when the highway opened up."

Six tunnels were blasted out between Squamish and North Vancouver. Thousands of pounds of dynamite were used and vast amounts of rock were removed.

Squamish Historical Society Video, courtesy www.squamishhistory.ca

When the Squamish Seaview Highway opened on Aug. 7, 1957, people reported rocks the size of footballs on the road. Rockfalls and slides were also a constant threat on the railway north to Whistler, where trains travelled at 40 km/h. The track, which is made up almost entirely of curves, also contains plenty of blind corners. The steepest incline is 2.2 per cent, up through the Checkamus Canyon. That's nearly a metre rise for every 30 m of track. The fear of a rock or a tree on the tracks was always very much on engineers' minds.

The potential for tourism in the Sea to Sky corridor was there long before the highway was constructed. Early Whistler settlers Myrtle and Alex Philip built Rainbow Lodge on the shores of Alta Lake (which doubled as the name of the nascent community at that time) in 1914. By the 1920s, the fishing lodge and guesthouse was one of Canada's most popular summer destinations west of the Rockies.

"They came out here from the Eastern U.S. and found this heaven on Earth that became Rainbow Lodge; (it) became one of the major stops on the railway for tourism," Mills recounts. "There was one passenger train a day out of Squamish before Rainbow Lodge went in. On Friday, there was the Fisherman's Special that would go up and come back on Sunday and ran until the mid-'50s."

Several lodges drawing on weekend tourism grew up along the railway. There were lodges at Alta Lake, Birken, D'Arcy and Seton Portage. The Bridge River town site had a first-class hotel and there were other lodges near Lillooet.

The potential for tourism in the corridor was summed up in 1952 when members of the powerful Vancouver Water Board, locked in a bitter conflict with advocates that wanted to put a highway through the Capilano watershed, said, "build the Howe Sound route where there's $10 million worth of scenery for tourists."

A HISTORY OF TOURISM

Rail service for tourism and industry has a prodigious track record in the Sea to Sky corridor. From 1949 until 1971, the railway connected logging and mining operations to the B.C. Interior and to Squamish, where resources could be transported by sea. The Pacific Great Eastern Railway line between Squamish and North Vancouver opened on Aug. 27, 1956. In 1972, the railway's name was changed to the British Columbia Railway and became known as BC Rail. In 1973, the Royal Hudson Steam locomotive was leased to BC Rail and an excursion service between North Vancouver and Squamish was started. The Royal Hudson ran five days a week between June and September. By the end of the 1974 tourist season, 47,295 passengers had been carried on the Royal Hudson, more than any other line in North America. The continent's only regularly scheduled steam excursion over mainline trackage at the time, the Royal Hudson quickly evolved into one of B.C's prominent tourist attractions.

But by February 1981, facing large losses and an aging fleet, BC Rail reduced its passenger operations to three trains a week to Lillooet. This led to public outcry, resulting in the B.C. government subsidizing passenger operations as of May 4, 1981.

"When the subsidies were dropped in 1991, BC Rail took the Royal Hudson over as part of their operations and had to subsidize it too," Mills explains.

In spite of these challenges, rail tourism continued to flourish. In 1997, BC Rail introduced the Pacific Starlight Dinner Train, which ran in the evenings from May to October between North Vancouver and Porteau Cove. But several money-losing services had resulted in BC Rail's workload increasing six-fold between 1991 and 2001. The Royal Hudson's steam train excursion service was discontinued in 2001 because the 2860 engine needed extensive repairs.

By 2001, BC Rail introduced the Whistler Northwind, a luxury excursion train that ran from May to October northbound from North Vancouver to Prince George and southbound from Prince George to Whistler. Both excursions were cancelled at the end of the 2002 season along with BC Rail's passenger service. Passenger service between Lillooet, Seton Portage and D'Arcy ended on Oct. 31, 2002 and was replaced by BC Rail with a pair of railbuses.

Critics of the closures said tourism and community life in communities along the line would be seriously impacted.

On Nov. 25, 2003, the B.C. Government sold the operations of the railway—excluding the right of way to Canadian National (CN) Railway—for $1 billion. The original lease for the rail right of way was for 60 years, with a 30-year option to renew. However, CN may have more opportunities for 60-year options to renew the lease and would not have to pay anything additional to keep operating for up to 900 years. At each renewal date, the province has the option of buying back all of the assets from CN.

"The whole passenger services system that BC Rail had worked quite well, and they were expanding and working on the Whistler Northwind Train from Whistler to Prince George," Mills says. "There just wasn't enough time to establish the service before the sale of BC Rail."

As of July 15, 2009, CN has the right to decommission any part of the line it wishes, but then the line would revert back to the Crown—though the province can sell the land back to CN for a dollar.

THE FUTURE OF REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION

The railroad endured and so has the highway. A rock scaler once said there are no more rockslides on the Sea to Sky Highway than on any other highway in B.C.—there's just a lot more traffic volume.

The $600-million upgrades to the highway were completed in 2009 in time for the following year's Olympics. The highway has steadily grown busier since then. In September 2018, 12,343 vehicles travelled between Squamish and Whistler and 21,725 vehicles travelled between Squamish and Horseshoe Bay on an average daily basis.

"In terms of going forward, we need to look at the capacity we have on Highway 99 and we need to understand what the growth perspectives are for businesses in Whistler and for development and growth in the whole corridor," says B.C. Liberal MLA for West Vancouver-Sea to Sky, Jordan Sturdy, who also serves as the official opposition critic for transportation and infrastructure.

To understand the corridor transportation issues, the Resort Municipality of Whistler, with the support of the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure, developed a Sea to Sky traffic model in 2016 that looked at traffic volumes from Horseshoe Bay to Pemberton over 10 to 15 years, factoring in approved development for the corridor.

In 2017, a BC Transit Sea to Sky Corridor Regional Transit Study received more than 2,000 responses, demonstrating a high level of interest among Sea to Sky residents for a regional service.

The most realistic possibility may be a bus service from North Vancouver connecting with Squamish, Whistler, Pemberton and Mount Currie.

"The buses would be public transit carrying commuters for work," explains Whistler Mayor Jack Crompton.

Municipal officials for the communities involved with the plan are hoping to have a funding model in place sometime in 2019.

The details of the schedule for this service still remain to be determined, and while anyone will be able to use it, the plan is to schedule the service to match the needs of working commuters.

The proposed funding model aims to minimize the impact on property taxes to as great a degree as possible. The model would see funding from riders, local and provincial governments, and a new motor-fuel tax to help offset the cost of the service. The cost of the system is directly related to the number of service hours: 15,100 annual service hours using eight buses on six roundtrips per day between Mount Currie and Pemberton to Whistler. There would be six roundtrips per weekday between Whistler, Squamish and Metro Vancouver. This would grow to 25,100 annual service hours and 13 buses by the third year, and to 30,000 annual service buses and 16 buses by the fifth year.

"The goal is to develop strong and effective regional transit," Crompton continues.

High-speed rail remains another issue. A spokesperson for the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure stated in an email that a feasibility study for high-speed rail service from Vancouver to Whistler would be part of any large infrastructure project that is being put forward.

Admittedly, high-speed rail would be extremely expensive and would be a future-looking endeavour. A feasibility study would assess a route from Vancouver to Whistler and stops along the way.

"Rail has to compete on a time basis, which is why the current alignment doesn't really work," Sturdy continued. "It also has to compete on location and operating costs. I would certainly favour that we look at how to connect a rail corridor in the Sea to Sky with a Translink system in an effective way."

The B.C. NDP has said it is open to working with local governments to explore new ideas if a compelling business case can be developed.

High-speed rail service from Vancouver to Squamish and Whistler could also reduce the risk to travellers, according to Mills.

"You'd have one driver and hundreds of people on a train all in one location," he says. "It's a lot safer than having hundreds of people in their own cars driving up and down."

To establish if the service is viable, the amount of daily rail traffic from Vancouver to Whistler would be determined by a feasibility study that looks at capital costs, demand forecasts and whether or not there is a business case for a proposal.

The challenge will be to trim the length of time it would take for the train to arrive in the resort.

"The mindset is that people want to get to Whistler quickly," Mills continues. "Vancouver to Whistler by train is almost double the time it takes to make the trip on the highway."

Rail travel would have to be at least roughly equivalent to highway travel times.

"It's all straightening out the curves," Mills says, "millions of dollars in blasting and rock cuts.

"There's one spot at Furry Creek where it's dead straight for about three quarters of a mile and that's it. Everything else is curves, tunnels, rock shelves and bridges."

A high-speed rail service from Vancouver to Whistler could have huge benefits for local tourism without increasing the density of traffic on Highway 99. Karen Goodwin, vice-president of destination and market development for Tourism Whistler, explains that tourists arriving at Vancouver International Airport travelling to Whistler can be broken down into two types.

"Your longer-haul traveller, your Brits or Australians, definitely will take the shuttle service that is provided from YVR up to Whistler. There are Americans and Canadians that will take the shuttle as well. I would say that a few more Americans like their rental cars and are comfortable driving."

A shuttle service is a smooth way to get skiers to Whistler, she adds.

"When you're in Whistler, if you have a car, you're going to park it and pay for parking and you don't really use it," Goodwin says. "Whistler is a pedestrian village."

About 44 per cent of skiing visitors take the roughly two-and-a-half hour shuttle to Whistler. Sixty per cent of destination winter visitors arrive by air.

With visitation records falling on a near annual basis, the Sea to Sky corridor will only get busier, and it will be difficult to persuade a regional visitor to leave their car at home unless there is a suitable rail or transit option.

"From a marketing perspective, we promote that our customers take the shuttle and not rent cars when they arrive at YVR," Goodwin says. "It's easier; you don't need a car when you get here. A train would provide an effective means of getting here and not having to deal with the highway."

In 2017, the B.C. Liberals stated in their platform that they would study the implementation of a commuter rail service from Vancouver to the corridor.

"It's worth thinking about that," then-Premier Christy Clark told The Daily Hive in a May 2017 interview. "Those rail options are things that we should be looking at because it's hard to build more and more roads, and lots of those rail lines are still there. If it's economical then we should be thinking about doing that in each and every case."

A major Texas-based development company that is already involved in Squamish's downtown waterfront redevelopment spearheaded the proposed commuter rail project. Matthews Southwest brought the proposal forward in late-2016, and said it would carry out a feasibility study to determine its potential cost, route, ridership, and business case.

However, there's uncertainty around whether the existing rail alignment from Horseshoe Bay to Whistler would be suitable for a high-speed rail service.

"We have to see whether there's a reasonable expectation that a business case could be generated," Sturdy reiterates. "We need to find out whether it's even realistic that we can have a trip that is less than two hours from Downtown Vancouver—and seamless."

With existing traffic volumes, there seems to be a misconception that Highway 99 has already hit its full capacity.

"That is, frankly, just not the case," Sturdy says. "The vast majority of travel times from Vancouver to Whistler are as good as they have been for the last five years."

The aim of high-speed rail is to maximize train performance by selecting a track alignment that optimizes the use of existing rail infrastructure while reducing or eliminating heavily curved segments by tunnelling or curve straightening. In building rail service to Vancouver, constraints such as existing communities, roadways, sensitive waterways and heavy canyon topography favour a tunnel under Burrard Inlet. The construction period for such a tunnel is estimated at between five and eight years.

This option would achieve a trip time from Waterfront Station to Whistler of one hour and 41 minutes, with an average train speed of 68 km per hour. To achieve a return on investment of all operating and capital costs, it appears that it would be necessary to carry 805 passengers per train. This is not an unrealistic figure considering the growth of Squamish.

"If it was a commuter service that was able to get you into Vancouver from Squamish in 40 minutes, one would imagine that the opportunities for Squamish could be quite significant," Sturdy says.

Questions remain: how would high-speed rail change the evolution of Squamish as a community, which is already increasingly becoming a bedroom community for Metro Vancouver?

"That's a pretty easy commute from downtown," Sturdy continues. "You'd get quite a few people looking at Squamish as a very viable commuting option."

Sturdy adds that the first step of a feasibility study would be "to look at various alignments, identify the additional challenges and risks—especially on the tunnelling side.

"Then determine whether we need to go to the next phase of assessment. At a high level, it may prove not to be realistic at this point in time, not with the volumes we would be potentially be looking at."

A high-speed rail service would have far-reaching impacts along the corridor and could actually accelerate population growth. It also would have very different repercussions depending on the community in question.

"If you're talking about Whistler, it's a transportation issue. It's ensuring that there's capacity there to serve the resort," Study notes. "If you're talking about Squamish, it's a transportation issue as well, but it's also a development issue. It will facilitate growth in Squamish where we look at community development and the evolution of Squamish as a different kind of community with a different kind of connection to Vancouver."

Sturdy is supportive of a feasibility study when it comes to understanding the impact that a high-speed rail service would have. There's also the persisting question of how much is enough?

"We've seen it in Whistler," Sturdy adds. "How big should Squamish grow? How quickly should it grow?

"Let's just get it on the table," he says of the study. "If it is compelling, then let's move through a lengthy process, spend time on the costs and how it would clearly work."

As Sturdy reminds us, with double-digit growth in the Sea to Sky, the time to learn the answers to these questions is now.

"We can't really wait for a decade to do anything about it."

Go here for the original story and more like it.