Following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police in May, a reckoning over racial justice has swept the United States and spread all over the world.

Squamish was not exempt from this.

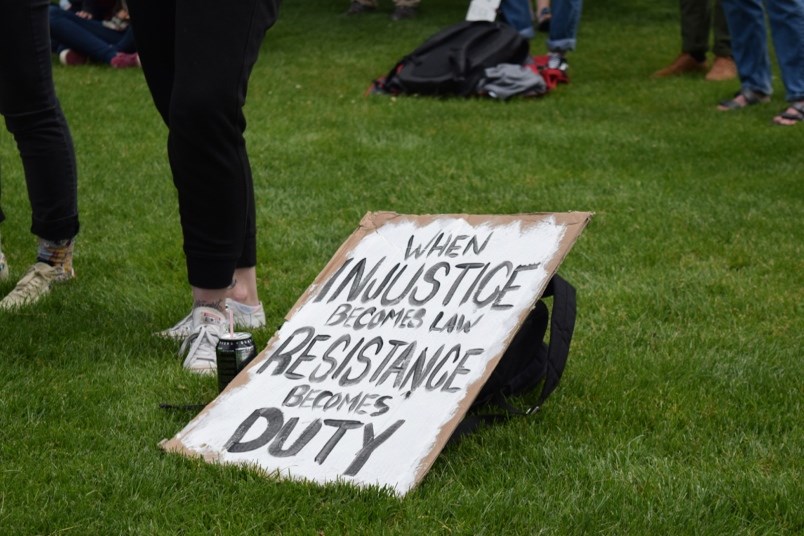

Here in town, hundreds gathered at O’Siyam pavilion as part of an anti-racism demonstration in June.

Shortly after, before council discussed RCMP funding, residents sent letters to elected officials that urged the politicians to defund the police.

Indeed, defunding the police has become a widespread mantra that is being repeated across the world and also in Squamish.

What does ‘defund the police’ mean?

Many of those demonstrating have advocated for taking at least some of the money allocated to police and placing it in services that would increase the welfare of the population and reduce the need for officers in the first place.

For example, that money could be directed to mental health supports, thereby reducing or eliminating the need for officers to respond to mental health calls, activists say.

These demonstrators also say that money directed to social services or education would increase opportunities and reduce poverty, thus reducing crime.

Officers in town have not gone unaffected by the rallying cry to defund them.

“I know for my police officers on the front line, it’s been deeply impacting,” said Insp. Kara Triance, the Sea to Sky’s officer-in-charge.

At the time, Triance was speaking to The Chief in August as the top cop in the Sea to Sky. However, as of this fall, she will be transferring to Kelowna.

“We’ve had police officers who’ve come home and had just terrible days out there. The language and sentiments towards the police have not been great. And then we’ve had the turn of support from a lot of people who’ve said, ‘Thank you.’”

In Squamish, the RCMP cost about $4.7 million in 2019, with the District of Squamish paying the lions’ share of roughly $4.6 million.

The municipality pays about 90% of the RCMP member costs and 100% of the costs for municipal support staff who assist the officers.

The Squamish force has the equivalent of about 25 full-time officers and also offers community policing and victim services. Each officer costs about $163,000 and altogether they account for roughly $3.9 million in municipal spending.

Some costs, like those for the victims’ services program, have increased over the years but not necessarily because of more crime.

Officers say that this is because policing is becoming more sophisticated and much more attention to detail is given to cases.

Triance said that as an example, a criminal harassment file from 2017 created a small mountain of paperwork.

“We had 2,000 pages of disclosure with 27 police officers from seven different agencies,” she recalled.

“That didn’t happen in the same regard when we were dealing with a file 20 years ago. And 20 years [ago], you didn’t have electronic disclosure. You had a short, six-page written — sometimes hand-written — report to Crown counsel. So policing has changed so much and I think if your question is, ‘Are we paying for policing in the right way,’ I think the complexities of it are so huge.”

Nevertheless, there are still some who think that money is better spent elsewhere.

“Systemic and institutional police bias towards racialized individuals and communities needs to be dismantled,” wrote Tricia Kerr in a letter to council in June.

“This isn’t just an American problem or a recent problem; this is present and well-documented in Canada. Council needs to address defunding the police. While this will broadly need to be addressed at the national level, the District of Squamish can still act at the municipal level and redirect funding for RCMP to local social programs and resources. Police reform has been unsuccessful and more attempts at reform will yield the same results.”

What follows is a discussion between authorities, a demonstrator and a racial justice educator about whether this protest slogan can or should be translated into a reality.

Squamish RCMP & the District

Authorities agreed that policing needs to be improved and re-examined, but the municipality and the RCMP stopped short of saying that they would outright support defunding the police.

Insp. Kara Triance said that Floyd’s death has rightfully prompted soul-searching in law enforcement.

“Canada hasn’t been removed from the impacts of this either. We are seeing that there are problems in policing across the country,” said Triance.

“And so we’ve had to really dig deep and look hard at the work that we’re doing to make sure we’re doing it well. But while we’re doing that, you’ve got to take care of your police officers. Because for me, if I’m not taking care of my police officers, and they’re going out there on the street, and feeling jaded and frustrated and not cared for and not well — this is when we’re going to see problems happen.”

Triance said policing needs to be re-examined, but she did not support defunding the force, as she said there aren’t societal structures in place to replace the work officers are doing.

“Defund the police isn’t an acceptable solution — we have to defund the police with a plan in place to make sure that’s replaced,” she said.

Authorities said that while systemic racism is a widespread problem, they said there is not enough data to conclude whether it exists in Squamish or not.

This also makes it hard to create a case for defunding the police. For example, it’s not always clear how many police calls could have been diverted to a mental health unit or another service.

“[There’s] a gap in data,” said Natasha Golbeck, the municipality’s general manager of community services. “If there’s one point that we really want to hit home, it’s better data.”

One big issue, said acting mayor Jenna Stoner, lies in how Canadian governance is structured. Stoner was sitting in for Elliott, as she was away during council’s summer break.

Municipalities are in charge of funding fire departments, police, roads, infrastructure and land use.

However, they are not responsible for education, social services or mental health support. Those responsibilities lie with the province.

Stoner noted that a major hurdle to transfering funds, as called for by demonstrators, is that if funding was taken from police, it would be unclear where that money would then go.

More money would be in municipal coffers, but the municipality would not be able to spend that cash on services that activists have outlined.

Instead, that money would likely have to be funneled to infrastructure projects, like roads, signage, sewage and other areas that are the responsibility of local governments — not social services or mental health.

“We can’t transfer that money to something like a mental health crisis unit, so we expect that the province will...put that money down. That is what their responsibility is under the health file,” said Stoner.

While some could argue that the municipality could use its community grants program to give the money to nonprofits like Helping Hands or Sea to Sky Community Services, Stoner said that there is a risk in this practice.

If the municipality does go that route, it risks creating a download of services from the province.

Then the municipality, with its fewer resources, would be left responsible for problems bigger than it can handle, she said.

Stoner also pointed to a letter that the District sent to the province, urging Safety Minister Mike Farnworth to explore ways to improve policing and recording data about officers’ interactions.

“As a municipal government, we recognize that a simple call to defund the police is not a solution. In fact, if we reduce our local governments’ police budget, that money would not go to mental health and addictions services — as that is provincial jurisdiction — but rather to roads, sewers, and other programs within our own jurisdiction. That said, as our local RCMP officers are called to respond to ever more mental health and overdose-related calls, we are in effect funding mental health and addictions services through our police force,” reads the letter sent by Elliott on June 30.

“In recognition of the complexity and multi- jurisdictional nature of this issue, the council of the District of Squamish is writing to: 1) request that a process be initiated in consultation with local government that allows us as a province to reimagine how we provide public safety and community health services; and 2) to call for transformative investments in the delivery of public safety.”

Triance said that at the moment, there’s no ability to break down statistics to show non-violent mental health calls. That is, mental health calls that could’ve instead been handled by a mental health or social worker instead.

“I can tell you the only mental health calls we attend are people in crisis. So we don’t attend for somebody who is not a risk to themselves or to others,” Triance said.

Triance also emphasized that Squamish RCMP have been trained and continue to be trained in cultural sensitivity, as well as the colonial legacy of the RCMP.

“True reconciliation is an acknowledgment that Canada was built on colonization, that the mounted police was sent to march west and that this is a police force that has colonial roots,” she said.

“Decolonization and reconciliation truly has got to look at that and say, ‘Yes we own a piece of that and how are we going to move together shoulder-to-shoulder ensuring we are policing in a violence-free manner and that we are ensuring that we change, and that we work together and that we move forward in a manner that is not racist.”

Speaking out

Jahmar Farrugia-Armstrong, who spoke at the Squamish anti-racism rally in June told The Chief that he believes that police should not be outright abolished, but that the system is profoundly flawed.

Many officers, he said, have their hearts in the right place, but the system is, in many cases, broken.

Canadian policing, in general, has deep-rooted problems — even if some people are refusing to acknowledge it, Farrugia-Armstrong said.

“It seems like systemic racism is deeply embedded in the core of law enforcement and policing. They use profiling. They use profiling to do their jobs every day,” he said.

In the case of authorities saying they couldn’t divert part of police municipal funding to mental or social services, he said he understood what authorities were saying, but had criticisms about those comments.

“I think there’s a problem at a system[ic] level that we need to look at and readjust. It seems like things aren’t set up properly in the first place. And now that we have a problem that we’re trying to fix here, they’re kind of throwing it back at us,” said Farrugia-Armstrong.

“It seems like the government needs more work than they’re willing to do to fix this problem.”

Farrugia-Armstrong also said that it’s incorrect to think that racism doesn’t exist in a town like Squamish. There is a tendency for people in smaller communities to believe that such problems are city problems only, but he noted that in small towns, minorities don’t have the same visibility.

“The problem with small towns is people of colour, minority people, don’t really have a big voice,” he said.

“And the small-town folks think they do. But that’s not really the case. Minorities tend to speak in a way that makes people feel comfortable around them, and if you’re in a small town surrounded by people that make you feel like the minority, you’re going...to say or do things that make other people feel comfortable and not necessarily challenge the status quo. Especially if you’re living a somewhat productive...lifestyle. You’re really not going to want to break that, especially when you see images of people that don’t have those things.”

Farrugia-Armstrong said that the fact that an anti-racism rally was held in Squamish should indicate that there are issues in the town.

He said that the RCMP needs to admit that one of their founding purposes was rooted in racist colonial practices, such as displacing Indigenous people from their lands.

It’s a good start the top cop in Squamish has acknowledged the colonial legacy of the force, but officers in town need to keep reaching out to communities, Farrugia-Armstrong said.

He also added that for healing to occur they need to be specific about what types of injustices were done, and not just vaguely say that bad things happened.

“If they’re not willing to come outright and just outright admit these atrocities and bear the weight of the effects of that past, which will inevitably be some emotional weight...I think until you actually start to do that, then you’re not going to have a system that can begin to heal or work for the people,” Farrugia-Armstrong said.

He said he believes most in the force are good, honest people with the right intentions, but the RCMP as an institution needs to come clean and fully admit its racist past, because the organization is in danger of corrupting from within.

“[Unless they do that] I believe what we need to do is replace these people,” he said.

“If people don’t want to give up the power, then you have to take the power away from them.”

Farrugia-Armstrong said he hopes that if the defunding movement for the police doesn’t work out, as an alternative, he would like to see new branches in the police department that can adequately deal with mental health and social service calls.

As one example, he said the Peel Regional Police in Ontario have created a mental health response program.

Under this program a crisis worker who is a registered nurse, registered social worker or occupational therapist is teamed up with a specially trained police officer to respond to mental health crisis calls.

Regarding the municipality’s writing a letter to Minister Farnworth, Farrugia-Armstrong said it was a good first step, but that without much other action, it’s an empty gesture.

He called for regular updates on how the lobbying is going and challenged authorities to show tangible results.

A local diversity, equity and inclusion educator centred on racial justice said that she agrees that with officials that defunding the police is not a silver bullet in a small town like Squamish.

Nadi Jones noted that defunding the police is an argument better suited to large American cities that have militarized their officers.

In those cases, it’s a more obvious choice to redirect funding that would be used for quasi-military equipment to social programs, Jones said. There are also differences in the funding structures and the amount of money police receive in the U.S..

As a result, Jones said it’s better for a community like Squamish to focus on training its officers to deal with their conscious or subconscious racial biases.

She said it’s possible to use psychological questionnaires to gauge how subjects feel about people of colour, and red flags could be dealt with either via training, or, if necessary, barring a potential recruit from entering the force.

“I’d say I want to make sure they’re doing the right kind of training. That they are investigating individuals’ anti-blackness and anti-Indigenous patterns and routines,” said Jones.

“It’s one thing to do training on making sure they’re collaborating with the community and make sure they’re using the right language and things like that, but it’s another thing to actually train individuals and as a team to understand those biases.”

An academic's perspective

SFU criminology professor Robert Gordon has a view that would likely not please either authorities or demonstrators.

On the one hand, he said that the defund the police movement is "sloganeering" that risks becoming a "knee-jerk" reaction. On the other hand, he supports completely disbanding the RCMP and replacing them with different police forces.

"The whole issue of defunding police as a catch-cry has accelerated," said Gordon. "It has legs because it's just such a sexy topic based upon a tragic situation, but we must be very, very careful as a society not to get drawn into this kind of hysteria….It's been a bane for many politicians who have been stuck with the task of trying to respond to something that makes no sense whatsoever."

Gordon also said the idea of taking money from an essential service like policing and having the municipality manage it could be risky.

"You've got to be careful where monies go," said Gordon. "Especially monies that are held by a municipality, which may not be the best body to hold the money, because it's too local and they're political. You could start seeing stuff shovelled off the back of trucks when you get to election time."

Concerning the municipality's assertion that insufficient policing data exists, he said that this likely stems from a decision made a long time ago in the Canadian policing world.

Gordon said that to prevent racial profiling, it was decided by authorities that data regarding race would not be collected.

Ironically, that has prevented a clearer picture regarding race and policing from emerging, he said.

Gordon also said he supports demilitarization and disbanding the RCMP.

He said the police service was created to clear First Nations off their land for European settlers. Later, they would help with rounding up children for the residential school system, and other oppressive activities.

"The whole organization as the Northwest Mounted Police was established to engage in systemic racism — that's a historical fact," Gordon said.

"They did a very effective job — that's not a compliment."

The collective memory of the RCMP is inculcated through centralized training at the depot in Regina, he said. As a result, negative attitudes to First Nations people live on this way.

"How you cleanse an organization of that I know not at this point. I think it's too late. I think that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police need to be disbanded and alternative policing organizations need to be brought in."

As a suggestion, he pointed to the Australian model, which has a federal policing service, along with provincial policing services.

"That way you break that cycle of oppression," said Gordon. "The organization's gone folks. You've got something entirely different."