You’ve just survived rape and made it to the emergency room of the Squamish Hospital. What happens next?

The first step is medical care to address any immediate physical needs, including addressing any concerns about infection, disease and pregnancy, according to Squamish public health nurse Nancy Skucas.

The second step, the sexual assault forensic exam, is optional. The exam, sometimes called a “rape kit,” is the collection of evidence that could be used in a police investigation of sexual assault.

“The whole entire time, the person – client – is in charge,” Skucas said, noting the victim can choose not to have the exam at all, and once the exam begins, the person can halt the process at any point.

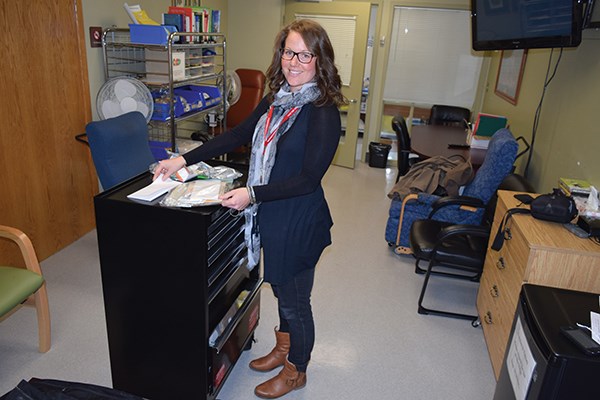

Skucas was recently trained to administer the forensic exam. She started her new role at Squamish General Hospital in December.

Previously, rape survivors in the corridor had to travel to the Lower Mainland’s Vancouver General Hospital after the assault to have the test done.

Skucas is available Monday to Friday.

With sexual assault, the primary service the forensic nurse provides the survivor is emotional support and crisis intervention, according to Skucas.

“They have gone through a pretty traumatic life event, and the fact they are able to come here – they are trusting you, so that means you are a big part of their life at that point in time,” she said, speaking softly and leaning forward as she emphasized her point. “Just letting them know that you truly believe them, that it wasn’t their fault.”

Skucas outlined each step of the forensic exam at Squamish General Hospital on Friday.

“Basically my job is to do a full, head-to-toe assessment wherever the client tells me they were assaulted,” Skucas said, adding the test is similar for men and women.

At various steps along the way, the patient is asked for consent for the test to continue, she stressed.

If there is evidence on clothes, such as blood or fluids, they are placed in envelopes.

Evidence such as paint chips, hair, fibres or debris is also collected. Skucas takes a mouth swab to collect the survivor’s DNA and collects other swabs, including dirt and dried blood. Fingernail clippings are taken if the survivor scratched the assailant. A genital exam may be performed.

Finally, a dye called Toludine Blue is applied to the genital area to check for any physical trauma.

The forensic testing can be done up to seven days after the assault, according to Skucas. Showering can eliminate some evidence, but the exam can still be done within that week timeframe, she said.

From start to finish, the exam takes about two hours.

After the patient leaves the hospital, Skucas writes up a report that is kept in a confidential area, she said. What happens to the evidence collected depends on what the person wants. If the patient is unsure if he or she wants the samples sent directly to police, the evidence is kept in a locked freezer at the hospital for up to a year. If the patient wants the evidence to go to the police directly, he or she signs a release, which is also signed by the nurse and a police officer.

Thirty-five per cent of women worldwide experienced either physical and or sexual violence in 2013, according to the World Health Organization.

Councillor Susan Chapelle, who has long lobbied for sexual assault services in the Sea to Sky Corridor, said not a day goes by when she doesn’t hear stories from people who have suffered sexual abuse, yet social services continue to struggle for basic funding.

“Women’s issues seem to remain a low priority despite talk of collaboration between service providers,” she said.

Vancouver Coastal Health funds the forensic exams, but the province has not provided extra monies for them, so the health authority has had to shuffle money from other programs around for it. According to Chapelle, no money was given for the administrative process that usually accompanies the exam.

“Scarce funds are taken away from one essential service in order to fund another.”

Chapelle said although having the sexual assault forensic exam available in Squamish is a step in the right direction, she fears without proper investment in the program, it may fail because the new nurse and trained doctors will be working without a coordinator to administer billing, time or resources.

“Having a forensic nurse in all hospitals is an essential service. It has not been funded with new investment; what is needed is new health-care dollars, not reallocated resources.”

The Squamish Chief contacted the Ministry of Health for comment but did not get a response by press deadline. A Vancouver Coastal Health spokesperson said the program is still in its early days, and officials are unsure how many cases the hospital will see.

“Time will allow us to get a better sense of what additional resources may be needed,” read the statement. “We want to assure the community that we are committed to this program, and there should be no questions about its viability.”

Shannon Cooley Herdman, Howe Sound Women’s Centre advocate for sexual assault response and prevention, said for reasons of stigma associated with sexualized violence, “this unique form of violence has been a neglected ‘cousin’ on the continuum of violence perpetrated against women and other vulnerable peoples.”

“It is not only timely but socially appropriate that our region becomes a leader in building robust sexual assault responses,” she said.

The centre is providing the forensic exam program with resource information for survivors to augment the new forensic testing program, according to Herdman.

A community service flow-chart is also being developed, along with a victims’ informational brochure on services available to sexual assault victims, both in the justice and social service sectors, she said.